- Published by:

- Victorian Aboriginal Heritage Council

- Date:

- 1 Jan 2021

Introduction

Culture is important for Aboriginal Peoples. Traditional Owners are the custodians of their heritage, the land, the waterways and the People.

Cultural Heritage is our lifeblood. As Traditional Owners, our Heritage is our relationship to Country – land and waters, the rocks, soil, plants, animals and all the things on it. Our Heritage connects us with each other. We look after Country, and it looks after us – body, heart and spirit. We want to make sure that the Culture is living, vital and continuing for many generations to come. We have that responsibility. It is our inherited and fundamental right, as custodians of the oldest living Culture on earth, to practice Culture and to set a vision for a strong future for our Cultural Heritage.

Culture is important for Aboriginal Peoples. Traditional Owners are the custodians of their heritage, the land, the waterways and the People. Cultural Heritage is intrinsically intertwined with Aboriginal Peoples’ knowledge, practices, community, objects and places which provide many with a sense of identity and culture. Aboriginal Cultural Heritage is passed through performance, written and verbal forms from generation to generation, and remains a fundamental part of the lived Aboriginal experience.

The passing of this knowledge has been impacted and disrupted through colonisation and government control over lands, waters and Cultural Heritage. Aboriginal Victorians seek to strengthen and reassert rights to connect, manage and control their Cultural Heritage.

Aim of this Discussion Paper

This Discussion Paper seeks feedback from Victorian Aboriginal Peoples about their Cultural Heritage management.

As First Peoples, we know who we are in our identity and in how we choose to live our customs and traditions

This Discussion Paper seeks feedback from Victorian Aboriginal Peoples about their Cultural Heritage management. It is part of the reporting mechanism in the Aboriginal Heritage Act 2006 (Vic) (AHA) - See Appendix 1 for information about the AHA. The AHA seeks to do this through the empowerment of Traditional Owners of Aboriginal Heritage to be protectors of their heritage by strengthening their spiritual, cultural, material and economic connection to it.

Every 5 years the Act requires a report on the State of Victoria’s Aboriginal Cultural Heritage (the Report). This is the first report developed by the Victorian Aboriginal Heritage Council and will reflect on:

- What is Cultural Heritage?

- What rights do Aboriginal Peoples want to Cultural Heritage?

- How are Aboriginal Peoples able to exercise these rights to Cultural Heritage currently?

- What stops Aboriginal Peoples from exercising their rights?

- How well does the wider Victorian community understand Aboriginal Cultures?

- What is the vision for the future?

This Paper seeks to promote dialogue on the state of Victoria’s Aboriginal Cultural Heritage.

It is important that we are able to empower People in communities to let them talk about their experience and let them articulate what Cultural Heritage is to them.

How to have your say

Your thoughts and feedback will provide the basis of a benchmark for where we are and where we can be in regard to protecting, managing and celebrating all Aboriginal Cultural Heritage in Victoria. Through thinking and talking about this Discussion Paper, you can help shape the pathway for current and future Traditional Owners to live their Culture through real and tangible ownership of their Country and management of Cultural Heritage.

Council is a body of Traditional Owners and we understand the sensitivities and hesitancies in providing feedback on a Discussion Paper such as this. We are not Government and we are not producing another document to sit on a shelf. We know what our mob think but we want to know what your mob think. Together, we can tell the world that these are the problems and the successes of how we manage Cultural Heritage in 2021 but that this is our vision of what our lived ownership of Culture and Country will be in 2026.

In working together with a shared vision, we can change the laws that should support us to manage and protect our Culture, the oldest living Culture on earth.

We would like to hear from Victoria’s Aboriginal Peoples and those individuals and organisations working with Victoria’s Aboriginal Peoples about the state of Aboriginal Cultural Heritage in Victoria.

You can do this by responding to the questions above and throughout this Discussion Paper by:

- visiting the VAHC website

- completing a survey on the above web page

- attending a consultation meeting to be held in Melbourne on February 11, 2021

- emailing your feedback to SOVACH@terrijanke.com.au

- phoning Laura Curtis or Anika Valenti from Terri Janke and Company on (02) 9693 2577

While each section of this Discussion Paper asks one main question, we have included additional questions to prompt discussion. You do not need to answer all the questions if you do not want to.

Please submit your responses to the Discussion Paper by 30 April 2021

A state-wide consultation will be conducted with key stakeholders and written submissions for the Report will be accepted to assist the critical analysis of the state of Victoria’s Aboriginal Cultural Heritage laws. The final Report on the State of Victoria’s Aboriginal Cultural Heritage 2016-2021 is intended to be finalised by the end of August 2021.

The past shapes our future: the historical context

The Aboriginal Heritage Act 2006 (Vic) (AHA) came into effect in 2007 to replace the ‘relics’ model of protection.

Our past influences the present, to go forward we need to understand the past and the journey that involves getting over the baggage that was thrust upon us. The hidden history needs to be brought out in the open and understood. This is where Cultural Heritage, native title and land justice will really benefit.

Firstly, let’s look at the past and see how far we have come...

Prior to the enactment of the AHA in 2006, Victoria had both State and Commonwealth legislation addressing protection of Cultural Heritage.

The Archaeological and Aboriginal Relics Preservation Act 1972 (Vic) was the first dedicated Aboriginal Heritage legislation in Victoria and provided protection for physical evidence of Aboriginal occupation before and after European occupation, including sites, scatters, artefacts, carvings, drawings and skeletal remains. The Act administered protection of Aboriginal Cultures as relics of the past. The focus remained largely on physical Cultural Heritage (sites and objects) with archaeologists the principal interest group consulted as opposed to Aboriginal communities, and failed to reflect that heritage is living – a product of the present as well as the past.4

Introduced in 1987, Part IIA of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Heritage Protection Act 1984 (Cth), provided wider protection for Aboriginal Cultural Heritage and gave Victorian Aboriginal Peoples a greater role in the protection of their heritage. The Heritage Act 1995 (Vic) established the Victorian Heritage Register for non-Aboriginal places and objects of outstanding significance to the state and the Heritage Inventory which is maintained by Heritage Victoria.

The Aboriginal Heritage Act 2006 (Vic) (AHA) came into effect in 2007 to replace the ‘relics’ model of protection and to align heritage issues more closely with planning and development systems.5 The AHA established the Victorian Aboriginal Heritage Council, being the first Victorian statutory body requiring members to be Traditional Owners, and Registered Aboriginal Parties (RAPs), to empower Traditional Owners to manage Country and Cultural Heritage at a local level. The AHA introduced the Cultural Heritage Management Plans (CHMPs) and Cultural Heritage Permits (CHPs) systems, higher penalties and stop orders, and the Victorian Aboriginal Heritage Register (maintained by Aboriginal Victoria). The Victorian Aboriginal Heritage Register is particularly remarkable as a central repository of Aboriginal Cultural Heritage information. Notably, this is a closed register and, other than the waterways, most information is not publicly accessible.

The 2016 amendments to the AHA brought Victorian laws to the forefront of Cultural Heritage protection in Australia, in particular with the introduction of protection measures for Aboriginal intangible heritage, including registration and the imposition of large penalties for commercial use of registered intangible heritage without permission. In addition, the 2016 amendments saw the responsibility of management, protection and repatriation of Aboriginal Ancestral Remains moved to the Council; expanded definitions and terms closer in line with Aboriginal concepts and understanding of those terms; Aboriginal Heritage Officers empowered to issue stop work orders for 24 hours; clarification as to when CHMPs are required; and the creation of Aboriginal advisory groups where no RAP exists to consult with.

Timeline

| 1972 |

Archaeological and Aboriginal Relics Act 1972 (Vic) and Part IIA Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Heritage Protection Act (Cth) – Joint ‘relics’ system for protection of Victorian Aboriginal Heritage in place until 2006. |

| 1979 |

The Australia ICOMOS (International Council on Monuments and Sites) Guidelines for the Conservation of Places of Cultural Significance was adopted at Burra, South Australia. It is generally referred to as the Burra Charter. |

| 1984 |

Successful law case initiated by Uncle Jim Berg for repatriation of Ancestral Remains from the Museum of Victoria. |

| 1985 |

Establishment of the Koorie Heritage Trust. |

| 1993 |

Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) comes into force - The first native title claim in Victoria was made by the Yorta Yorta People in 1994, but in 1998 the Federal Court determined that native title did not exist over the claim area. It wasn’t until June 2004 that the Yorta Yorta People entered into a Cooperative Management Agreement with the Victorian Government to give effect to their rights to land and water. |

| 1995 |

Heritage Act 1995 (Vic) – Introduced overarching state legislation for historical sites in Victoria and provided for registration, and subsequent protection and conservation, of places and objects of Cultural Heritage significance. The Heritage Act establishes the Victorian Heritage Council, the Victorian Heritage Register and the Heritage Inventory. All non-Aboriginal archaeological sites in Victoria more than 50 years old are protected under the Act. Archaeological sites such as cemeteries or missions which may have a combination of both historic and Aboriginal heritage values are protected under the AHA.6 |

| 2004 |

Budj Bim Cultural Landscape included on National Heritage List. |

| 2006 |

Aboriginal Heritage Act 2006 (Vic) - Replaced the Archaeological and Aboriginal Relics Preservation Act 1972 (Vic) and Part IIA of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Heritage Protection Act 1984 (Cth) for protection of Aboriginal Cultural Heritage. |

| 2010 |

Traditional Owner Settlement Act 2010 (Vic) – Introduced as a comprehensive, non-litigated claims process that provided an alternative to native title that Traditional Owners could use to gain rights to country and settle native title claims in Victoria. The Victorian Government has identified self-determination and partnerships as foundational to the Act, and rights include recognition of Traditional Owners of Country, funding, and use and management of natural resources.7 |

| 2013 |

Though adopted in 1979, the Burra Charter is updated periodically. The current version was adopted in 2013. Set up of Bunjilaka at Museum Victoria & establishment of Yulendj group (members of the Bunjilaka Community Reference Group). |

| 2016 |

Aboriginal Heritage Amendment Act 2016 (Vic) - Amended the AHA to improve reporting requirements in relation to Aboriginal Cultural Heritage, to introduce provisions regarding Aboriginal intangible heritage, and to establish an Aboriginal Cultural Heritage Fund. |

| 2017 |

Yarra River Protection (Wilip-gin Birrarung murron) Act 2017 (Vic). May 2017 – Uluru Statement from the Heart, a gift to the Australian people, calling for a First Nations voice in the Constitution and the establishment of a Makarrata Commission to oversee the process of agreement making between governments and First Nations and truth telling. |

| 2018 |

Advancing the Treaty Process with Aboriginal Victorians Act 2018 (Vic) (Treaty Act). |

| 2019 |

Budj Bim Cultural Landscape inscribed on World Heritage List. First Peoples’ Assembly of Victoria established on 9 Dec 2019 under Treaty Act. |

Auntie Eleanor A. Bourke, ex-Chairperson of the Victorian Aboriginal Heritage Council remembers the past denialism of Aboriginal existence and the lack of rights stemming from justification of invasion:

It’s because of the history of dispossession and dislocation. In the beginning, when you’re a colonised society, people really don’t want you there because you remind them of the bad things that have been done in taking over the country. There’s whole waves of experiences that people have, right up until when we got the protection phase, which lasted for about 60 years in Victoria, where people thought we were going to die out, that was the general belief.8

Over a career working in Cultural Heritage policy, Bourke pointed out in the Council’s 10 Year Anniversary Report, "Aboriginal Cultural Heritage is now managed by Registered Aboriginal Parties (RAPs) in more than fifty percent of the state."9 This percentage has increased to 74%, and the Council has a clear goal of seeing RAPs appointed with respect to the whole of the State.10 In a recent interview she proudly stated - 'My goal is to see that recognition of Traditional Owner groups is carried through to all aspects of everyday life, beyond just Cultural Heritage matters.' 11

While the AHA and the 2016 amendments have introduced positive change and altered the previous outdated focus on protection of relics, there exists ‘a general lack of understanding about how the heritage protection system currently works’,12 and more needs to be done to ensure appropriate control of Cultural Heritage by Victorian Aboriginal Peoples into the future.

Where are we now? Current threats to Victorian Aboriginal Cultural Heritage

There remain significant threats to Aboriginal Cultural Heritage in Victoria.

The Aboriginal Heritage Act and [UN] Declaration [on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples], together, provide some of the greatest protections for Traditional Owners in the country. However, there is still much to be done in realising a fundamentally self-determined and tangible ownership of our Culture, Heritage, History and Country.

There remain significant threats to Aboriginal Cultural Heritage in Victoria.

The AHA sets up a system for developers of land to obtain clearance where Cultural Heritage sites are potentially impacted. The AHA readily facilitates a ‘salvage’ mentality of removal of sites for development rather than empowering Aboriginal self-determination to control, manage, protect and retain their Cultural Heritage. The shift from protection to self-determination is occurring in some respects with the development of the Traditional Owner Settlement Act (TOSA), but to deliver the goals for Aboriginal Peoples to manage and control their heritage will take much more.

In addition:

- there is limited collaboration and consideration undertaken prior to destruction of sites

- museums and archives continue to hold much of Victorian Aboriginal Peoples’ Cultural Heritage

- intangible property is recognised but considered separately from tangible Cultural Heritage, and the registration system has not been taken up effectively

NOTE: As of October 2020, there has only been one registration of intangible heritage on the Aboriginal Heritage Register.

Finally, both the AHA and the TOSA that followed in 2010 provide rights to Traditional Owners over Country, causing overlap, potential confusion and administrative burdens for Traditional Owners.

Since the 2016 amendments to the AHA, there have been many projects, both State and private, that have caused damage and destruction to Aboriginal sites and Cultural Heritage. The vast majority of the damage and destruction has been legal and in accordance with the CHMP system under the AHA.

Some of the more immediate threats include:

- lack of Cultural mapping – Only approx. 6% of the state has been surveyed for Cultural Heritage

- unnamed waterway, including tributaries

- private housing development,

- State infrastructure

- private and State land use practices,

- State emergency management practices,

- major changes to landscape, including clearing of native bushland and levelling of dunes,

- public use of State managed land and deliberate damage,

- erosion and other natural processes.

The CHMP process has some significant flaws. A CHMP assesses the potential impact of a proposed development activity on Aboriginal Cultural Heritage registered within the activity area or found during the standard and complex assessments. The intention is that RAPs are then empowered to stipulate the measures to be taken before, during and after the activity to manage and protect the Aboriginal Cultural Heritage within the activity area. The practice of this process, however, compromises this intention. To highlight just a few of the weaknesses of this process, here are a few observations:

- A sponsor (project proponent) generally approaches the CHMP process as a ‘check box’ exercise. Actual engagement with the cultural significance of a site is superficial. In many instances the sponsor’s ideal outcome is to move through this process with minimal disruption to their development plan (and timeline).

- RAPs have insufficient authority in the process. RAPs are part of the process, but they cannot conclusively control the outcome of the proposed activity or the impact on Cultural Heritage. Appeal to VCAT is often prohibitively expensive, and the prospects of success appear to be slim.

- The archaeological analysis of a site is too narrow. The archaeological techniques used as well as the parameters for what they are searching is very restrictive and skews the ultimate outcome and ‘ranking’ of significance.

Each year approximately 600 Cultural Heritage Management Plans are undertaken to manage the protection of our Cultural Heritage. Stronger enforcement measures came into effect with the 2016 amendments to the Act. But our heritage is still being destroyed and it breaks my heart.

Discussion question: What are the current threats to Aboriginal Cultural Heritage in Victoria?

- What have been the major impacts to Aboriginal Cultural Heritage in Victoria since 2016?

- How can these pressures and threats be addressed?

- What is needed for Aboriginal Peoples to have greater control over the CHMP process and protection of their Cultural Heritage?

Culture is living: Importance of Victorian Aboriginal Cultural Heritage

Aboriginal Cultural Heritage comprises the intangible and tangible aspects of the whole body of cultural practices, resources and knowledge systems.

The health and wellbeing of our communities is underpinned by strong culture and a strong sense of connection with it.15

Aboriginal Cultural Heritage comprises the intangible and tangible aspects of the whole body of cultural practices, resources and knowledge systems that have been and continue to be developed, nurtured, refined and passed on by Aboriginal Peoples as part of expressing their cultural identity.16 It creates and maintains continuous links between People, lands and waters. It shapes identity and is a lived spirituality fundamental to the wellbeing of communities through connectedness across generations.17

The AHA seeks to protect Aboriginal Cultural Heritage through the empowerment of Traditional Owners as protectors of their heritage by strengthening their right to maintain their spiritual, Cultural material and economic connection to it.18 In implementing the aims of the AHA, the Victorian Aboriginal Heritage Council’s purpose is to ensure

Traditional Owner led management, protection, education and enjoyment of Aboriginal Cultural Heritage for the benefit of all Victorians.19

Strong, healthy relationships require cultural safety, particularly when building relationships with non-Indigenous Victorians. An environment of respect, where Aboriginal Peoples feel that they can share their Culture without risking harm through disrespect or misuse is imperative. Relationships are the central way that Aboriginal Peoples can build their connections to their Cultural Heritage whilst connection to Country is intrinsically connected to the health and wellbeing of Aboriginal Peoples. The importance of the link to land, significant Cultural sites waterways and People and identity cannot be overlooked in legislation that aims to empower Aboriginal Peoples in the protection of their Cultural Heritage.

Ensuring that the image is there around kinship – We have kinship as People but can’t have it without Country – it is connected to the Country.

The shift in thinking from protection and salvage to caring for Culture through in-situ care and building relationships is illustrated in the following diagram:

Figure 1: Shift in thinking and approach to caring for culture

Protection

- Cultural Objects as ‘relics’

- Entrenched tangible/intangible thinking

- Principal interest group = archeologists

- Preservation and salvage approach

- Culture held in state museums

- Advisory capacity instead of decision-making authority

Taking care of culture

- In-situ care and ICIP Protocols for use of Cultural belonging

- Aboriginal communities - principal decision makers

- Self-determination & management

- Truth telling by those with Cultural authority

- Living Cultural Practice

- Caring for Country

- Communities are decision makers and have enforcement powers

- Wholistic view of people, Culture, and Country replaces tangible/intangible binary

The AHA defines Aboriginal Cultural Heritage as Aboriginal places, objects and Ancestral Remains. However, considering Cultural Heritage is a living cultural practice that includes what is considered intangible heritage, this definition doesn’t appear to go far enough.

Discussion question: Tell us what you think about Cultural Heritage as a living cultural practice?

- What does Aboriginal Cultural Heritage mean to you?

- How do Aboriginal Peoples want to connect with Aboriginal Cultural Heritage?

- In what way can Aboriginal Peoples realise their interaction with Cultural Heritage?

- Does the definition in the AHA cover this? If not, how should it be defined?

- How should the state of Victoria’s Aboriginal Cultural Heritage be assessed?

- What indicators should be used to assess the state of Victoria’s Aboriginal Cultural Heritage?

How Aboriginal culture is understood by Victorians

Victorian Aboriginal Peoples have a strong understanding of their culture, heritage and spirituality, and recognition and appreciation of Aboriginal Cultural Heritage amongst non-Indigenous Victorians continues to grow.

It is our Cultural Heritage, but if we don’t bring other People in, then they won’t understand our connection to Country.

Victorian Aboriginal Peoples have a strong understanding of their culture, heritage and spirituality, and recognition and appreciation of Aboriginal Cultural Heritage amongst non-Indigenous Victorians continues to grow. This extends to support for policy change to improve processes for recognition, protection and management of Aboriginal Cultural Heritage.

Examples of new approaches to the protection of Cultural Heritage include the Yarra River Protection (Wilip-gin Birrarung murron) Act 2017 (Vic) which provides an important acknowledgment of Aboriginal values in river management and protection, and the listing of The Budj Bim Cultural Landscape as a UNESCO World Heritage site, the first ever world heritage site recognised solely for its Indigenous Cultural values.

In May 2018, the membership of the Heritage Chairs and Officials of Australia and New Zealand (HCOANZ) expanded to include Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander chairs. Together the expanded HCOANZ created a vision for the care of Indigenous Australians’ heritage into the next decade:

- Dhawura Ngilan: A vision for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander heritage in Australia.

- The Best Practice Standards in Indigenous Cultural Heritage Management and Legislation was published in September 2020.20

Both provide a guide to improving approaches to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander heritage management in Australia. Truth telling is key to the vision as is the intention to become a world leader in the preservation, celebration and promotion of First Nations’ Cultures.

While there may be public appreciation of Aboriginal Cultural Heritage and a growing momentum to ensure improved systems of protection and Aboriginal engagement and control of Cultural Heritage at the State and National level, do Victorian’s have an appropriate level of understanding and respect for Aboriginal Culture?

In 2017, the Bunjilaka Aboriginal Cultural Centre at Melbourne Museum exhibited Black Day, Sun Rises, Blood Runs identifying stories of the atrocities of colonisation including massacre sites that have historically been whitewashed.

Back in the day we were struggling to get Traditional Owners at the table to manage Cultural Heritage, but we campaigned and were successful in getting the Aboriginal Heritage Act up which gave Traditional Owners primacy in managing their own culture. We cannot be left out of the conversation about caring for our Country and managing our culture. Traditional Owners have managed to successfully sign settlement agreements with Government, and this has influenced Cultural Heritage policy reform. Traditional Owners have to be front and centre – we must benefit Culturally, economically and spiritually.

Discussion question: Do Victorians understand the importance of Cultural Heritage?

- What level of understanding do Victorians have about Victorian Aboriginal Cultures?

- How do Victorians learn about Aboriginal Cultures?

- Is Aboriginal Cultural Heritage taught in schools?

- How can general understanding of Aboriginal Cultures and Cultural Heritage be improved?

Self-determination and Aboriginal control: Management of Aboriginal cultural heritage in Victoria

The fundamental principles of self-determination and Aboriginal control and management of cultural heritage are enshrined in the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

We need to use our voice, to strengthen our identity and increase participation in the ways of working to ensure we are provided opportunities for self-determination in all areas of Culture.

The fundamental principles of self-determination and Aboriginal control and management of Cultural Heritage are enshrined in the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UN Declaration) and other international instruments.21

The AHA is considered by some to be progressive in how it deals with Aboriginal Cultural Heritage in Australia in comparison to other states and territories, but this is not necessarily a difficult measure to achieve. The Victorian Government has committed to self-determination as the guiding principle in Aboriginal affairs and to ‘working closely with the Aboriginal community to drive action and improve outcomes’.22 However, the AHA is yet to truly embed these principles or the UN Declaration’s related obligation for free, prior informed consent (FPIC) for impacts to Cultural Heritage.

Aboriginal Peoples involvement in Cultural Heritage management remains primarily in the form of consultation and advice, rather than formal decision-making (with some exceptions), and there is a lack of legal avenues or formal rights for Aboriginal Peoples seeking to enforce protections of their heritage.23 As identified in the State of Indigenous Cultural Heritage report that accompanied the 2011 Commonwealth State of the Environment report:

A revision of the framework for determining the ‘condition’ of Indigenous heritage is needed, driven by Indigenous stakeholders, to better reflect Indigenous heritage, particularly in relation to the role of cultural practices and the relationship between Indigenous ‘heritage’, ‘culture’, ‘traditional knowledge’ and Australia’s lands, waters and natural resources. 24

There is currently no consistency across jurisdictions in relation to the protection and management of Aboriginal Cultural Heritage, but each of the Commonwealth and State and Territory governments are taking steps to review their approaches. For example:

- The Australian Government has commissioned an independent review of Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (Cth) to among other things, improve heritage listings and consultation processes for heritage places25, and is working with the Australian Heritage Council to promote best practice engagement with Indigenous People, including FPIC for assessments and listings.

- In 2018, the draft Aboriginal Cultural Heritage Bill 2018 (NSW) (Bill) providing for a new framework for the management of Aboriginal Cultural Heritage was released for consultation in NSW. Heritage NSW and Aboriginal Affairs are currently working on finalising the Bill pursuant to public feedback.26

- The Heritage Amendment Act 2020 (ACT) took effect in the ACT on 26 February 2020, introducing amendments to the Aboriginal Heritage Act 2004 (ACT) providing for a more flexible and responsible system of heritage directions and compliance notifications to strengthen the way damage to heritage places and sites is dealt with.

- The Western Australia Government in consultation with the Aboriginal Advisory Council of WA is developing a Biodiscovery Bill which seeks to provide an accreditation or certification regime in WA in accordance with the Nagoya Protocol on Access and Benefit Sharing.

The Victorian Aboriginal Heritage Council is also advocating for a review of the AHA. In June 2020, the Council issued Taking Control of Our Heritage, a Discussion Paper calling for further reforms to the AHA. The key discussion points included:

- RAPs need to be Local Government’s primary authority on all matters relating to Aboriginal Cultural Heritage, both tangible and intangible.

- Sponsors should be required to consult with RAPs from the outset of the CHMP process.

- RAPs should have a veto power over CHMPs that threaten harm to Aboriginal Cultural Heritage.

- The Victorian Aboriginal Heritage Council should hold responsibility of the Victorian Aboriginal Heritage Register.

- The Victorian Aboriginal Heritage Council should hold the rights and responsibilities of prosecution.

- That there should be a regulation system for Heritage Advisors.

The consultation period for the Discussion Paper closed on 30 November 2020 and Recommendations for changes to the Act will be made in early 2021.

Other mechanisms for self-determination of Victorian Aboriginal Peoples include the nation-leading work towards a Treaty currently being undertaken in accordance with the Advancing the Treaty Process with Aboriginal Victorians Act 2018 (Vic). On 9 December 2019, the First Peoples’ Assembly of Victoria was declared to be the Aboriginal Representative Body, independently reporting to the Parliament of Victoria each year on progress towards negotiation of a treaty.

The Assembly released their first annual report on 15 September 2020.

Traditional Owners of Victoria have never before engaged with Parliament on equal terms. The Assembly is Parliament’s sovereign equal, comprising democratically elected Members who have been honoured with the responsibility of representing and advocating for Traditional Owners, and the broader Victorian Aboriginal Community

Mick Harding, Member of the Victorian Aboriginal Heritage Council, considers that there is also the need for Aboriginal Peoples to be in leading political positions: "Having an Aboriginal person who is Minister for Aboriginal Affairs, or [being] promised seats in parliament. [It is important to have] our person as the head in Government."

Discussion question: What are the current measures in place that promote self-determination and Aboriginal control of Aboriginal Cultural Heritage in Victoria?

- Why does Victoria need to have good Cultural Heritage protection?

- Is the current regulatory framework (the AHA, NT and TOSA) effective for the protection of Aboriginal Cultural Heritage?

- What are the strengths?

- What are the weaknesses?

- What are the gaps in the law?

- How do Aboriginal Peoples want to see Cultural Heritage managed?

- How can the current regulatory framework be improved?

Land is our future: Caring for Country

Aboriginal Peoples have a deep connection with land and waters with Country, which is central to their spiritual identity, and have maintained this connection despite the devastating impacts of colonisation and forced removal.

Cultural Heritage is the legacy we inherited from our Ancestors. And it includes responsibilities to protect both the physical aspects – land, water, flora, fauna and today, archaeology; and the intangible aspects - our story, language, mythology and lore. Our Ancestors understood that caring for Country allowed Country to care for them.

Aboriginal Peoples have a deep connection with land and water with Country, which is central to their spiritual identity, and have maintained this connection despite the devastating impacts of colonisation and forced removal. Unlike modern Australian perceptions, land is not just a commodity to be owed and used, but rather a place of belonging as well as way of connecting to one’s Culture, Spirit, People and identity.

Aboriginal Peoples have the fundamental right, as enshrined in the UN Declaration, to control, manage and care for Country. This includes the right to be involved in decisions relating to the access, use and development of Country, and to ensure appropriate care and protection is maintained for future generations.

Secret or Sacred Objects are a big part of who we are. They carry the stories that shape us, and we, and future generations, in turn shape them. They need to be with their rightful custodians so they can keep carrying our stories and our connections with them.

Legislation like the AHA which is designed to protect Aboriginal Cultural Heritage, empower Traditional Owners as protectors of their Cultural Heritage and promote respect for Aboriginal Cultural Heritage, must ensure that Traditional Owners are afforded the capability – legal and otherwise - to enforce these rights. As currently drafted, the AHA has been called ‘reactive not proactive’ in the protection of Aboriginal Cultural Heritage, and certain lands are exempt from its application i.e. those controlled by the Australian Defence Force.

The Budj Bim listing really breaks new ground in regard to not only how UNESCO responds to it and ICOMOS, but the Australian Government and the Victorian Government. It was a real vindication and a surprise for those other countries to recognise the work that we’ve done as Gunditjmara People, the broader community, the Australian and Victorian Governments, that we’ve produced what they consider best practice.

Currently, the AHA affords Traditional Owners some rights in relation to development through the CHMP and CHP systems. However, many community members consider these systems to be a "box ticking" exercise for developers (often large development companies with immense resources) to ensure their planning application is approved.

While giving Traditional Owners the power to be a part of the process, the current system does not allow Traditional Owners to comprehensively control the outcome of a project on Country.

This may mean that Traditional Owners are provided less flexibility under the AHA than the system under Part IIA of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Heritage Protection Act 1984 (Cth). Under the Commonwealth Act, material evidence still had to be found within the footprint of the

proposed activity and management of parts of activity where Cultural Heritage had yet to be found was possible. However, under the AHA, management only takes place in areas that have been proven to contain Cultural Heritage.

As Mick Harding from the Victorian Aboriginal Heritage Council highlights:

We [Traditional Owners] do get to have the final say and put in recommendations [under the current CHMP system], but more often than not it’s about destruction – all we get is salvage. Who is to say we can reconstruct the place by imagination? If that place and space is there, then [we] can paint a clearer picture of the heritage.

There is at least some shift occurring and movement away from the tick-the-box approach to engaging with the project’s Traditional Owners of that Country from the start. A residential housing development in Kalkallo, a locality within the Wurundjeri Woi Wurrung Cultural Heritage Aboriginal Corporation RAP area, is an example of a more consultative approach with Traditional Owners. This approach led to the retention and incorporation of numerous sites occurring along the watercourses and on top of stony rises as opposed to the more common large-scale salvage and resulting destruction of sites.

Positive models of Aboriginal self-determination and collaboration for Victorian Traditional Owners caring for Country have and continue to be developed including natural resource management and joint management of national and state parks. Through the TOSA, Traditional Owners

groups have been able to develop and enter into plans with Parks Victoria for the appropriate management of park lands and waters.

There has also been the return and revitalisation of cultural practices enabling Traditional Owners to care directly for Country, from fire management and ranger programs to the development of economic opportunities through tourism, research, bush foods and interpretation.

The Dja Dja Wurrung Clans Aboriginal Corporation, the RAP for the central Victorian goldfields, has received Federal Government support to research the viability of growing commercial levels of Kangaroo Grass. Once a vegetation plentiful across Victoria’s open grasslands, the grass once harvested and milled by Ancestors is being used by Traditional Owners as a means to grow smarter, more sustainable agricultural products and support the organisation.

Discussion question: What does caring for Country mean for you?

- How do Aboriginal Peoples want to interact with Country and with sites?

- How can Aboriginal Peoples be empowered to care for Country?

- What measures would empower Aboriginal Peoples to effectively pass on knowledge about Country and sites to future generations?

Waters are our spirit

Aboriginal Peoples in Victoria have a deep connection with waters and waterways.

Water effects the dreaming places, environmental flooding impacts Aboriginal Cultural Heritage.

Aboriginal Peoples in Victoria have a deep connection with waters and waterways. They are essential to Spiritual and Cultural practices, as well as environmental management, food production, language and (Lore) law. Water connects People and communities to land, and to each other.

Aboriginal Peoples have a right to control and manage their waters under NT and TOSA. This includes the right to co-design environmental management plans relating to, or impacting, waterways, as well as the right to control access and use of their waterways. Aboriginal Peoples also have the right to share in the economic opportunities derived from the use of water and waterways, and the use of their water knowledge in resource management.

Currently, there are some laws in place that recognise Traditional Ownership of waterways, and the role of Aboriginal-led water management. In 2018, for example, the Historic Shipwrecks Act 1976 (Cth) was replaced with the Underwater Cultural Heritage Act 2018 (Cth) to include all underwater heritage.

In 2017, the Yarra River Protection (Wilip-gin Birrarung murron) Act 2017 (Vic) established the statutory body, the Birrarung Council, as the independent voice of the Yarra River. At least two members of the Council must be nominated from the Wurundjeri Woi Wurrung Cultural Heritage Aboriginal Corporation to ensure appropriate caring of the river.

There is also developing policy, for example, the VAHC project Our Places Our Names – Waterways Naming Project. Through this project, RAPs and Traditional Owners are encouraged to apply to the relevant naming authority to change the registered name of a waterway and to name currently unnamed waterways. The renaming of waterways with language names is an important process of decolonising the landscape, as it replaces the names given by European settlers with that place’s Aboriginal name. Changing the registered name and updating the VICNAMES dataset reasserts Traditional Ownership of the waterways and means that language names will appear on such things as road signs and Google Maps.30 The naming of currently unnamed waterways will afford a level of protection for a vast number of unregistered places and objects within the landscape currently not possible.

The Murray Lower Darling Rivers Indigenous Nations (MLDRIN) was established in 1998 and is a confederation of 25 sovereign First Nations from the southern part of the Murray Darling Basin. The MLDRIN has a number of functions including capacity building for participation of their First Nations members in government decisions on natural resource management and advancing their First Nations members’ rights to own and manage their water resources.31

The Aboriginal water program run by the Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning (DELWP) has a number of programs running, including the Dja Dja Wurrung Clans capacity building project at Bendigo Creek, and the Gunditj Mirring and Barengi Gadjin Towards Cultural Flows Project at the Glenelg River. The Aboriginal water program aims to better include Victorian Aboriginal Peoples in the way water is managed in Victoria and to empower community connection to water for cultural, economic, customary and spiritual purposes.32

CHMPs have produced some positive outcomes. Grampians Wimmera Mallee Water (GWMWater) worked on a CHMP for the Wimmera Mallee Pipeline with the Barengi Gadjin Land Council Aboriginal Corporation, the local RAP and Native Title holders for the Wotjobaluk, Jaadwa, Jadawadjali, Wergaia and Japagulk Peoples for the Native Title area around the Wimmera River. GWMWater reported that they developed a ‘very successful working relationship’ with the Land Council on that project.33

On 12 November 2020, it was announced that the Gunaikurnai Land and Waters Aboriginal Corporation will receive two gigalitres of unallocated water in the Mitchell River. In addition, Southern Rural Water (the water corporation responsible for administering the Mitchel River Basin Local Management Plan) will make a further four gigalitres of unallocated water available on the open market over 2020 and 2021.34

This comes after introduction of the Water and Catchment Legislation Amendment Act 2019 (Vic), which amended the Water Act 1989 (Vic) and the Catchment and Land Protection Act 1994 (Vic).35 The amendments embed Aboriginal cultural values into the planning and operations of water resource management. For example, the Water Act 1989 (Vic) now reads that a Sustainable Water Strategy must consider opportunities to provide for Aboriginal cultural values and uses of waterways in the region to which the Strategy applies.36

Nevertheless, more can be done to empower the ownership and control of Traditional Owners over their water and waterways, and more can be done to ensure that Traditional Owners receive equitable benefits over the use and management of their resources. In fact, in some circumstances, waterways are left at active risk of harm through a failure to recognise their cultural and environmental significance. For example, the current definition of waterways in the AHA excludes many ‘unnamed’ waterways including tributaries. This has permitted harmful activities to take place there because they are not afforded the protections of the AHA.

NOTE: The breadth of destruction is difficult to quantify as there are thousands of objects and sites associated with unnamed waterways that are currently unregistered so are unmapped.

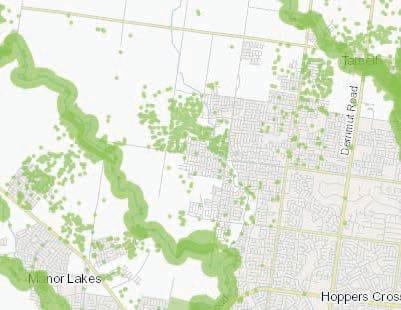

Figure 2: Areas of Cultural heritage sensitivity, Tarneit and surrounds

Note the number of sites of cultural sensitivity in close proximity to unnamed waterways. Source: Aboriginal Cultural Heritage Register and Information System (ACHRIS)

In the map (Figure 2), the green areas represent areas of Cultural Heritage Sensitivity. Cultural Heritage Sensitivity is defined in the Aboriginal Heritage Regulations 2018 (Vic) to include registered Cultural Heritage places and specific areas listed in Schedule 1 of the Regulations.37 The larger areas have been known as areas of Cultural Heritage Sensitivity since the first version of the Regulations was adopted in 2007.

The individual dots are recorded sites, individual artefacts or Low-Density Artefact Distributions (LDADs). They are now registered areas of Cultural Heritage Sensitivity, but they were not always so. They were only recognised as areas of Cultural Heritage Sensitivity because the developments or projects undertaken within that location either included already registered sites within the activity area, which is rare in Greenfields developments38, or the developments were large enough to include areas of Cultural Heritage Sensitivity and as a result, the detailed site assessment that followed found the new recorded sites.

Although it cannot be definitively said these sites are where they are because of their proximity to unnamed waterways, it does demonstrate the likelihood for areas of Cultural Heritage Sensitivity to be beyond 200m of named waterways. In addition, the fact that the smaller sites are recorded only because developments or projects were undertaken in the area suggests there may be many more unrecorded sites in proximity to unnamed waterways.

Discussion question: What are your Cultural responsibilities when it comes to caring for water and waterways?

- How do Aboriginal Peoples want to interact with waters?

- What measures would empower Aboriginal Peoples to effectively pass on knowledge about their waters to future generations?

- How can Aboriginal Peoples be empowered to care for water?

Plants and animals

Plants and animals are totems for Aboriginal Peoples.

The impact of the loss of our totem animals is enormous. When our totem dies, our connection with the spirit is compromised. The spirit and totem are as one and once our totem dies, a bit of our spirit dies as well. We feel the whole of Country in ourselves and its loss is felt in our whole spirit, not just the body that carries the spirit.

Plants and animals are totems for Aboriginal Peoples. Aboriginal Peoples share the land with them and their relationship is fundamental to the continued practice, and cultural responsibility – for food, health, shelter, cultural expression and spiritual wellbeing. Caring for plants, animals and their habitats is therefore seen as a keyway of expressing culture. In 2019 at the University of Melbourne the Living Pavilion was an Aboriginal led project that connected Indigenous Knowledge, ecological science, sustainable design and participatory arts. Over 40,000 Kulin Nation plants were installed to represent local Aboriginal perspectives, histories and culture.39

Indigenous ecological knowledge of Country, including knowledge of plants and animals, has sustained life and been passed on by Aboriginal Peoples for tens of thousands of years, and remains distinctive to each Aboriginal clan and language group in Victoria. With the expanding recognition of the unique qualities of Australia’s native plants and animals in Australia and Internationally, there has been rapid growth in research, development and commercialisation of bushfoods, medicines and products, with the Australian native foods industry alone estimated to be worth approximately $20 million in 2019.40

Unfortunately, the majority of the development and growth of the native foods industry and use of Indigenous medicinal knowledge in the pharmaceutical and cosmetics industries have been led by non-Indigenous industry and businesses, utilising Indigenous ecological knowledge to its own advantage without co-design or benefit sharing with Traditional Owners and communities.

At the inaugural Indigenous Native Foods Symposium held in Sydney in October 2019, it was determined that Indigenous businesses represent only 2% of the providers across the supply chain in the native foods industry despite being the providers of the knowledge on which the industry is based.41

There has only been fragmented approaches at the national and state level to implement best practice International obligations concerning conservation of biodiversity resources (plants and animals) and fair and equitable sharing of benefits with Indigenous People - See Appendix 2 for more information about the UNESCO Convention on Biological Diversity and the Nagoya Protocol. Victoria recently updated its Flora

and Fauna Guarantee Act 1988 (Vic) - the key biodiversity legislation in Victoria – to incorporate consideration of the rights and interests of Traditional Owners, however these amendments stop significantly short of the access and benefit sharing obligations of International instruments.

There are great opportunities for Traditional Owner groups and the wider Aboriginal community to develop and commercialise their knowledge through bush products and tourism ventures on Country already. It is imperative that Aboriginal Peoples also actively engage with and guide the future growth of industries incorporating Indigenous ecological knowledge to ensure appropriate collaboration, consultation, free prior informed consent, access, benefit sharing and commercialisation arrangements.

Discussion question: How are plants and animals looked after as Cultural Heritage of Aboriginal Peoples?

- How do Aboriginal Peoples want to connect with plants and animals?

- How should non-Indigenous business and industry work with Aboriginal Peoples in the development of industries that use their plants and animals and knowledge?

- In what ways can Aboriginal Peoples be empowered to control and manage the use of plants and animals e.g. caring for forests etc?

- How can Aboriginal Peoples control dissemination of their knowledge about plants and animals?

- How should Aboriginal Peoples be involved in the industries that use their plants, animals and knowledge e.g. native foods industry?

Cultural objects

Victoria’s museums and archives are now home to many objects of enormous cultural significance to Victoria’s Aboriginal Peoples.

Every time Aboriginal Cultural Heritage becomes artefacts – they’re removed from Country, categorised and catalogued – it is not what they were intended for…removal of them then can be seen as an ongoing manifestation of our Peoples’ dispossession from Country.

Victoria’s museums and archives are now home to many objects of enormous cultural significance to Victoria’s Aboriginal Peoples. These include Secret or Sacred Objects, art, possum skin cloaks, photographs, weapons, hunting tools and fish traps. In many cases these objects were at some point stolen from their communities of origin, or at least obtained under circumstances which would not meet the standard of free, prior, informed consent if acquired today. Lack of knowledge and care has meant that many of these objects have a history of storage and treatment that did not recognise their significance and was inconsistent with cultural protocols.

Western styles of catalogue management have prioritised recording of certain information and have neglected other forms of information. For example, a catalogue entry for an archival photograph may record the anthropologist’s name but not the names of any of the Aboriginal People in the frame. This bias in record keeping has meant the loss of a great deal of significant cultural information.

When displayed in exhibitions, curation and explanatory panels, in short, the wholistic interpretation of the object is frequently designed by a non-Indigenous person who does not have the requisite knowledge or authority to be telling that object’s story in a way that is authentic. Historically, the very absence of Aboriginal voices in all stages of collections care and management has produced a deafening silence in the walls of what is already an essentially western institution.

All that we are is story. From the moment we are born to the time we continue on our spirit journey; we are involved in the creation of the story of our time here. It is what we arrive with. It is all we leave behind. We are not the things we accumulate. We are not the things we deem important. We are story. All of us. What comes to matter then is the creation of the best possible story we can while we-re here; you, me, us, together. When we can do that and we take the time to share those stories with each other, we get bigger inside, we see each other, we recognize our kinship – we change the world one story at a time.

That said, the Galleries, Libraries, Archives and Museum (GLAM) sector has, on the whole, been ready to acknowledge its challenges, and proactive in the adoption of best practice models of collection acquisition, management, care and display. Some have also displayed an active shift to truth telling activities through co-design of exhibitions, and Aboriginal-led interpretation however, as a sector, there is still a lot more to be done in understanding the CHA.

The Bunjilaka Aboriginal Cultural Centre within Melbourne Museum, a venue of Museums Victoria includes a permanent exhibition space showing First Peoples, an exhibition co-designed by Aboriginal People, as well as an art space, the Birrarung Gallery, which holds three exhibitions a year showing the work of contemporary Aboriginal artists. Bunjilaka also includes the Milari Garden where plants of significance to the First Peoples of Victoria are grown as well as Kalaya, their performance space.42

In addition to an exhibition space dedicated to Aboriginal art and culture, the Koorie Heritage Trust offers cultural education services, cultural competency training, and a Koorie Family History Service. They have had their Oral History Collection since 1987 and now have over 2,000 recordings, primarily from Aboriginal People from all over Victoria.

The GLAM sector has a role to play in truth telling. It also has a role in building its own capacity to facilitate revitalisation and maintenance of connections between cultural objects, cultural practice and their Traditional Owners.

Discussion question: Why is it important for Aboriginal Peoples to control the management and care of their Cultural objects?

- How do Aboriginal Peoples want to connect with their cultural objects?

- How can Aboriginal Peoples be empowered be the interpreters of their Cultural objects?

- How can Aboriginal Peoples be involved in the co-design of conservation and collection management plans for objects in GLAM sector collections?

- What are some two-way learning opportunities between Aboriginal communities and the GLAM sector?

Art and performance

Aboriginal Peoples have the right to practice and revitalise their Cultural Traditions, to develop manifestations of their culture including performing arts.

Engagement with the arts can have powerful impacts on health, wellbeing and the strengthening of communities…The role of the arts in exploring and communicating social concerns, giving voice to hidden issues and allowing self-expression is also a major contributor to health. 43

Aboriginal Peoples have the right to practice and revitalise their Cultural Traditions, to develop manifestations of their culture including performing arts.44

Art and Performance has a powerful impact on the social, emotional, physical and cultural wellbeing of all Australians. Victoria has a vibrant Aboriginal Art and Performance sector. In addition to the positive wellbeing outcomes of a thriving Arts and Performance sector, there are significant economic opportunities for People who work in the sector.

Song and performance allow us to maintain memory and language. Being creative enables us to pay respect to our traditional practices, our Ancestors, our Culture in ways that may have been considered lost but that have always been present.

The Torch provides art, cultural and arts vocational support to Aboriginal offenders and ex-offenders in Victoria. Through a range of programs and initiatives it enables artists, both emerging and established, within the prison system to find pathways to wellness and future financial stability through art.

The Short Black Opera is a national Indigenous not-for-profit organisation, based in Melbourne. They provide training and performance opportunities for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander performing artists. One of their projects is the Ensemble Dutala, Australia’s first Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander chamber ensemble.45

Ilbijerri is a Woiwurrung word meaning ‘Coming Together for Ceremony’. The ILBIJERRI Theatre Company is one of Australia’s leading theatre companies, creating works by First Nations artists. Just recently, in July, ILBIJERRI put on a special online showing of Jack Charles v The Crown.46

The Koorie Heritage Trust is currently showing several online exhibitions including, an exhibition of Daen Sansbury-Smith’s work, called Black Crow47 and a group show called Affirmation, a photographic exhibition that explores the concept of truth in the context of place, Ancestral identity and cultural pride. The group show includes photographs by Paola Balla, Deanne Dilson, Tashara Roberts and Pierra Van Sparkes.48

VicHealth, an independent statutory body reporting to the Minister for Heath, has a health promotion framework for Aboriginal Victorians. The framework identified the Arts as a priority setting for action. VicHealth has supported a number of community driven arts initiatives including:

- The Black Arm Band: an ensemble of musicians drawn from Aboriginal communities across Australia.

- Songlines Aboriginal Music Corporation: Victoria’s peak Aboriginal music body.

- The Fitzroy/Collingwood Parkies DVD History Project: the project involves collating into a documentary, interviews with nine community elders, film footage and historical resources about the Aboriginal People known as the Fitzroy/ Collingwood Parkies group.

On the national level, the Indigenous Visual Arts Industry Support program, run by the Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development and Communications supports around 80 Indigenous arts centres and a number of art fairs, regional hubs and industry service organisations around Australia. In Victoria in this financial year, they are funding the Aboriginal Corporation for Frankston and Mornington Peninsula Indigenous Artists, the Gallery Kaiela Incorporated and the Koorie Heritage Trust.

Given the health, cultural and economic opportunities derived from a prosperous Arts and Performance sector, it is important to build the capacity of this sector. As evidenced above, there are many projects currently being actively pursued. Nevertheless, the

sector relies too heavily on the enthusiasm and commitment of its talent to paper over the significant administrative and financial challenges of building a career in the arts. The casualisation of the workforce for example created financial uncertainty for arts workers even before the current pandemic.

In addition, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander creatives must contend with the short comings of Australia’s intellectual property laws in the protection of their Indigenous Cultural and Intellectual Property. The very purpose of IP law is to incentivise creativity. However, when cultural designs, stories and dances can be copied and used by People with no connection to the source community, and without permission of Traditional Owners, without any legal repercussions, this can make Aboriginal creatives weary of sharing their knowledge and creative output. This economic lens doesn’t even begin to address the significant risk of cultural harm that can occur when cultural knowledge is used without consent, or misappropriated.

Discussion question: How do communities’ benefit from a vibrant and sustainable arts and performance sector?

- What can be done to strengthen the Arts and Performance sector?

- What measures would empower Aboriginal creatives to share their creative output?

- How can we build culturally safe environments in the Arts and Performance Sector?

Language

Before the start of colonisation there were around 40 Aboriginal languages spoken in Victoria.

Language places you within society, it also tells you of the lores, tells you of your stories, and it’s your spiritual connection to Country as well.49

Before the start of colonisation there were around 40 Aboriginal languages spoken in Victoria. They were (and are) connected to Country. For example, languages from Country located along the coastline had complex references to marine systems.50

Colonisation caused many of these Aboriginal languages to go into decline. Complex language systems that had developed over thousands of years, were no longer regularly spoken. The Victorian Aboriginal Corporation for Languages (VACL) was established in 1994. VACL works in language revitalisation by retrieving, recording and researching Victorian Aboriginal languages. They are the peak body for Victorian Aboriginal languages. They assist local communities in their language revitalisation plans. They run language camps, workshops, school programs and networking events. They create language resources (including digital resources and dictionaries), publications and music.

Language is an Ancestral right…Language contributes to the wellbeing of Aboriginal communities, strengthens ties between Elders and young People and improves education in general for Indigenous People of all ages.

One such project is the digitisation of Gunai/ Kurnai story books. In this project six Gunai/ Kurnai Story books are being converted into digital storybook apps.

They are also involved in languages programs in schools, including the Robinvale P-12 College, Thornbury Primary School and Healesville High School.

The Victorian Curriculum and Assessment Authority (VCAA), collaborated with the Victorian Aboriginal Education Association Inc (VAEAI) and VACL to create the Marrung Aboriginal Education Plan (2016 – 2026) and Victorian Curriculum Foundation-10: Victorian Aboriginal Languages curriculum.

Victorian government schools are also required to comply with the Koorie Cross-Curricular Protocols for Victorian Government Schools.

In Victoria language revitalisation is an on-going process. Language and culture is living and is practiced on a daily basis. Language revitalisation work continues, in part through the success of the Certificate III in Learning an Endangered Aboriginal Language and Certificate IV in Teaching an Endangered Aboriginal Language.

2019 was the International Year of Indigenous Languages and PULiiMA, Australia’s Indigenous Language and Technology Conference, had its biggest year yet with over 600 delegates attending, 120 presenters, 25 intensive workshops and 30 exhibitors.51 In the same year UNESCO and the government of Mexico, in co-operation with regional, national and international partners, agreed to the Los Pinos Declaration recognising 2022-2032 as the International Decade of Indigenous languages.52

Discussion question: In what ways does language revitalisation, strengthen culture?

- What can be done to further revitalise languages in Victoria?

- What can be done to ensure that Aboriginal Peoples manage and control use of language in Victoria?

- What empowers intergenerational transmission of language?

Traditional knowledge

For Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People, traditional knowledge includes ecological knowledge, medicinal knowledge, environmental management knowledge and cultural and spiritual knowledge.

Intellectual Property Organisation (WIPO)’s Draft Articles for The Protection of Traditional Knowledge as:

knowledge that is created, maintained, and developed by Indigenous peoples, [and] local communities…and that is linked with, or is an integral part of, the…social identity and/or Cultural Heritage of Indigenous peoples [or] local communities; that is transmitted between or from generation to generation…which subsists in codified, oral or other forms; and which may be dynamic and evolving, and may take the form of know-how, skills, innovations, practices, teachings or learnings.53

The UN Declaration sets out that Indigenous Peoples have the right to maintain, control, protect and develop their traditional knowledge.54

For Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People, Traditional Knowledge includes ecological knowledge, medicinal knowledge, environmental management knowledge and cultural and spiritual knowledge. It includes technical knowledge and know-how, agricultural knowledge, and astronomy.

In fact, Traditional Knowledge is constantly being added to as it is passed down from generation to generation. The word ‘Traditional’ refers to the act of passing on through intergenerational knowledge systems. It does not mean that it is old and static. Traditional knowledge continues to be a living Cultural practice.

Traditional knowledge systems are inextricably linked to People and country. Although much Traditional knowledge is passed on through walking Country, talking with Elders, sharing songs, stories and dance, it is also closely linked to cultural objects. Traditional knowledge is also carried in digital records (e.g. e-books, catalogues, datasets etc) giving rise to issues of data sovereignty. So, the tangible/intangible distinction made in western dialogue about Cultural Heritage, is a bit misleading in the context of Aboriginal Cultural Heritage. Nevertheless, the AHA allows for the registration of Aboriginal intangible heritage on the Victorian Aboriginal Cultural Heritage Register. A RAP, registered native title holder, or Traditional Owner group can apply to have intangible heritage recorded on the Register. Once entered onto the Register, that intangible heritage cannot be used for commercial purposes without the registered owners’ consent. It has been said that a significant drawback of this protection is that any knowledge widely known to the public, by definition, cannot be intangible heritage.

A significant aspect of caring for traditional knowledge is to ensure that Victorians commit to the internationally recognised standard of free, prior, informed consent (FPIC) whenever working with Aboriginal Peoples, communities or knowledge. Compliance with FPIC empowers Aboriginal communities to set the terms of use of traditional knowledge by other Victorians.

Discussion question: What are the ways that traditional knowledge can be cared for and shared in culturally safe ways?

- How can intergenerational transmission of cultural practices be facilitated?

- What can be done to care for culture and ensure intergenerational transmission?

- Given that traditional knowledge and cultural objects are inextricable linked, what can museums and archives do to facilitate Aboriginal Peoples’ caring for culture responsibilities?

- What are the key features that you expect to see in an FPIC process?

Aboriginal Cultural Heritage Register - intangible heritage

The 2016 amendments to the AHA recognised Aboriginal intangible heritage, introduced a system for recording intangible heritage on the Aboriginal Cultural Heritage Register.

The 2016 amendments to the AHA recognised Aboriginal intangible heritage, introduced a system for recording intangible heritage on the Aboriginal Cultural Heritage Register, and made it an offence to use registered intangible heritage for commercial purposes without consent of the relevant registered owner. The amendments further incorporated Aboriginal intangible heritage agreements between registered owners and third parties to define those uses that could be made of registered heritage.

Aboriginal intangible heritage is defined in the AHA as knowledge or expression of Aboriginal tradition, including oral traditions, performing arts, stories, rituals, festivals, social practices, craft, visual arts, environmental and ecological knowledge, and intellectual creations or innovations derived from these, but excludes Cultural Heritage and anything widely known to the public.55

The obvious limitation with the definition of Aboriginal intangible heritage in the AHA is that it is separated from the definition of Cultural Heritage. All heritage is linked, not only to particular land and waters but to Aboriginal Peoples, their spirituality and their identity. You cannot have one without the other, and if this is not appropriately expressed in the guiding legislation, then Cultural Heritage cannot properly be understood or protected by wider community. In addition, the protection under the AHA only extends to intangible heritage that is not widely known by the public. This begs the question whether Aboriginal Cultural Heritage loses its "cultural worth" just because it is no longer secret.

Understandably, Aboriginal Peoples would resoundingly disagree with this notion. Limitations to the registrability of intangible heritage is misguided and leads to ineffective protection.

The registration of intangible property on the Aboriginal Cultural Heritage Register has proven decidedly ineffective as only one registration of intangible heritage on the Aboriginal Heritage Register has occurred since provisions were introduced into the AHA in 2016. Some concerns raised by Traditional Owners have been the absence of heritage overlay in the registration, the need to provide sensitive cultural knowledge to non-Traditional Owners, public servants and the lack of tangible outcome.

Discussion question: What are the advantages/challenges of recording Aboriginal Cultural Heritage in a register?

- How do the definitions in the AHA need to change to ensure appropriate interpretation of Aboriginal Cultural Heritage?

- What have been the issues registering intangible heritage on the Aboriginal Cultural Heritage Register?

- How should intangible heritage be protected?

- How can the registration system be improved?

Respecting those who came before: Ancestral Remains

Since colonisation there has been large scale – public and private – theft of Ancestral Remains and ceremonial objects from Aboriginal burial grounds.

Our spirit cannot rest when our Old People’s remains are not in place. By repatriating their remains to rest, we reset time and space to allow their spirit to continue its journey.

Since colonisation there has been large scale – public and private – theft of Ancestral Remains and ceremonial objects from Aboriginal burial grounds.

Museum Victoria (MV) actively acquired Ancestral Remains by conducting archaeological digs and encouraging members of the public to hand Ancestral Remains to the MV. The Murray Black and Berry collections held at the University of Melbourne, included over 1,600 Ancestral Remains, some as old as 14,000 years. The justification for this desecration was "scientific research". It wasn’t until the 1980s that the Archaeological and Aboriginal Relics Act 1972 (Vic) made the possession or display of Ancestral Remains by institutions an offence. Though entirely too belated, this measure at least provided a foundation for further advocacy for repatriation of Ancestral Remains. In 1985, 38 Ancestors from across Victoria were reburied in Kings Domain, Melbourne.56

These portrayals [of sacred objects for "educational purposes"] are nothing, but ongoing colonial propaganda designed to justify the theft and detention of our objects and Ancestors.

The UN Declaration sets clear standards in relation to respect for Indigenous Peoples ceremonial objects and human remains. Indigenous Peoples have the right to use and control their ceremonial objects and to the repatriation of their Ancestral Remains.57

In Victoria, the AHA oversees the repatriation of the Ancestral Remains of Aboriginal Victorians and the return of Secret or Sacred Objects. Under the AHA, any person is obligated to notify the VAHC if they are in possession of human remains that they have reason to believe are Aboriginal Ancestral Remains. Similarly, if a person comes into possession of Secret or Sacred Objects after 2016, they must notify the VAHC. In particular, any public entities (such as museums) or universities were obligated to notify the VAHC if they were in possession of Ancestral Remains, within two years of the rule’s introduction in 2016. At this point in time, all public entities and universities should have already performed this obligation.

Given that the obligations in relation to Secret or Sacred Objects are slightly less stringent than those for Ancestral Remains – the obligation only applies if the person comes into the possession of the objects after 2016 – there are additional provisions relating to public institutions and universities in possession of Secret or Sacred Objects. In the case of universities, museums, or other institutions, if an Aboriginal person with an ownership claim over a Secret or Sacred Object requests the repatriation of that object, the institution must comply by repatriating the objects to the Traditional Owners directly or transferring the object to the possession of the VAHC. Following a 2016 amendment, an ‘ownership claim’ is established if a person is a Traditional Owner of an area in which the object is reasonably believed to have originated.

The VAHC then has the responsibility of arranging for the repatriation of Ancestral Remains and Secret or Sacred Objects to the Traditional Owners or RAP, as the representative Traditional Owner body, determined to be the owners of the Ancestral Remains or Secret or Sacred Objects and are willing to take custody of the Ancestral Remains or objects. All unprovenanced Ancestral Remains or Ancestral Remains and Secret or Sacred Objects that are yet to be returned to the RAP or the appropriate Traditional Owners are managed by the Council.

Heavy fines follow the infringement of any of these legal obligations.

These provisions of the AHA go a long way to meeting the standards of UN Declaration. In additional to meeting the standards under Article 12, this model of repatriation follows Articles 3 and 4 (the rights of self-determination and self-government in relation to Aboriginal internal affairs) because the oversight and repatriation activities are managed by the VAHC, a statutory body representing Aboriginal Victorians.

However, there remain limitations to the AHA. In particular, the AHA does not apply interstate or internationally meaning it does not apply to any Ancestral Remains or ceremonial objects transferred interstate, or overseas (for example to UK institutions).

Beyond repatriation of Ancestral Remains, protection and management of traditional Aboriginal burial places is also a concern. Many burial places are at risk from human activity and environmental damage. Traditional Owners are reluctant to reveal the location of these burial places to authorities and the VAHC has noted a lack of financial resources to support long-term strategies.58

Discussion question: How can Aboriginal peoples be further empowered to manage the care of their Ancestral Remains and ceremonial objects?

- What, if anything, can be done to improve co-ordination of the management and return of Ancestral Remains and ceremonial objects?

- What measures do you believe would help to develop understanding of the importance of Ancestral Remains across the whole Victorian community?

Giving voice to people: Revitalistion of cultural heritage practices

Aboriginal People hold distinct Cultural Rights and must not be denied the right to enjoy their identity and culture, their language, their kinship ties and their spiritual, material and economic relationship with the land and waters with which they have a Traditional connection.

Our Cultural Heritage is best understood through demonstrating respect for Traditional Owners – our knowledge, our skills, our appreciation of our heritage. The practicing of our culture and traditions makes us stronger and this strength offers all Victorians opportunities to value, understand and celebrate the unique Cultural Heritage we care for on behalf of all of us.

Section 19(2) of the Charter of Human Rights and Responsibilities Act 2006 (Vic) states that Aboriginal persons hold distinct Cultural Rights and must not be denied the right to enjoy their identity and Culture, their language, their kinship ties and their spiritual, material and economic relationship with the land and waters with which they have a Traditional connection.