Water effects the dreaming places, environmental flooding impacts Aboriginal Cultural Heritage.

Aboriginal Peoples in Victoria have a deep connection with waters and waterways. They are essential to Spiritual and Cultural practices, as well as environmental management, food production, language and (Lore) law. Water connects People and communities to land, and to each other.

Aboriginal Peoples have a right to control and manage their waters under NT and TOSA. This includes the right to co-design environmental management plans relating to, or impacting, waterways, as well as the right to control access and use of their waterways. Aboriginal Peoples also have the right to share in the economic opportunities derived from the use of water and waterways, and the use of their water knowledge in resource management.

Currently, there are some laws in place that recognise Traditional Ownership of waterways, and the role of Aboriginal-led water management. In 2018, for example, the Historic Shipwrecks Act 1976 (Cth) was replaced with the Underwater Cultural Heritage Act 2018 (Cth) to include all underwater heritage.

In 2017, the Yarra River Protection (Wilip-gin Birrarung murron) Act 2017 (Vic) established the statutory body, the Birrarung Council, as the independent voice of the Yarra River. At least two members of the Council must be nominated from the Wurundjeri Woi Wurrung Cultural Heritage Aboriginal Corporation to ensure appropriate caring of the river.

There is also developing policy, for example, the VAHC project Our Places Our Names – Waterways Naming Project. Through this project, RAPs and Traditional Owners are encouraged to apply to the relevant naming authority to change the registered name of a waterway and to name currently unnamed waterways. The renaming of waterways with language names is an important process of decolonising the landscape, as it replaces the names given by European settlers with that place’s Aboriginal name. Changing the registered name and updating the VICNAMES dataset reasserts Traditional Ownership of the waterways and means that language names will appear on such things as road signs and Google Maps.30 The naming of currently unnamed waterways will afford a level of protection for a vast number of unregistered places and objects within the landscape currently not possible.

The Murray Lower Darling Rivers Indigenous Nations (MLDRIN) was established in 1998 and is a confederation of 25 sovereign First Nations from the southern part of the Murray Darling Basin. The MLDRIN has a number of functions including capacity building for participation of their First Nations members in government decisions on natural resource management and advancing their First Nations members’ rights to own and manage their water resources.31

The Aboriginal water program run by the Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning (DELWP) has a number of programs running, including the Dja Dja Wurrung Clans capacity building project at Bendigo Creek, and the Gunditj Mirring and Barengi Gadjin Towards Cultural Flows Project at the Glenelg River. The Aboriginal water program aims to better include Victorian Aboriginal Peoples in the way water is managed in Victoria and to empower community connection to water for cultural, economic, customary and spiritual purposes.32

CHMPs have produced some positive outcomes. Grampians Wimmera Mallee Water (GWMWater) worked on a CHMP for the Wimmera Mallee Pipeline with the Barengi Gadjin Land Council Aboriginal Corporation, the local RAP and Native Title holders for the Wotjobaluk, Jaadwa, Jadawadjali, Wergaia and Japagulk Peoples for the Native Title area around the Wimmera River. GWMWater reported that they developed a ‘very successful working relationship’ with the Land Council on that project.33

On 12 November 2020, it was announced that the Gunaikurnai Land and Waters Aboriginal Corporation will receive two gigalitres of unallocated water in the Mitchell River. In addition, Southern Rural Water (the water corporation responsible for administering the Mitchel River Basin Local Management Plan) will make a further four gigalitres of unallocated water available on the open market over 2020 and 2021.34

This comes after introduction of the Water and Catchment Legislation Amendment Act 2019 (Vic), which amended the Water Act 1989 (Vic) and the Catchment and Land Protection Act 1994 (Vic).35 The amendments embed Aboriginal cultural values into the planning and operations of water resource management. For example, the Water Act 1989 (Vic) now reads that a Sustainable Water Strategy must consider opportunities to provide for Aboriginal cultural values and uses of waterways in the region to which the Strategy applies.36

Nevertheless, more can be done to empower the ownership and control of Traditional Owners over their water and waterways, and more can be done to ensure that Traditional Owners receive equitable benefits over the use and management of their resources. In fact, in some circumstances, waterways are left at active risk of harm through a failure to recognise their cultural and environmental significance. For example, the current definition of waterways in the AHA excludes many ‘unnamed’ waterways including tributaries. This has permitted harmful activities to take place there because they are not afforded the protections of the AHA.

NOTE: The breadth of destruction is difficult to quantify as there are thousands of objects and sites associated with unnamed waterways that are currently unregistered so are unmapped.

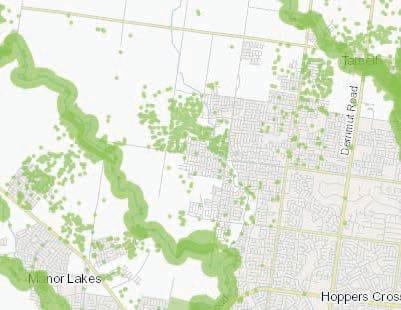

Figure 2: Areas of Cultural heritage sensitivity, Tarneit and surrounds

Note the number of sites of cultural sensitivity in close proximity to unnamed waterways. Source: Aboriginal Cultural Heritage Register and Information System (ACHRIS)

In the map (Figure 2), the green areas represent areas of Cultural Heritage Sensitivity. Cultural Heritage Sensitivity is defined in the Aboriginal Heritage Regulations 2018 (Vic) to include registered Cultural Heritage places and specific areas listed in Schedule 1 of the Regulations.37 The larger areas have been known as areas of Cultural Heritage Sensitivity since the first version of the Regulations was adopted in 2007.

The individual dots are recorded sites, individual artefacts or Low-Density Artefact Distributions (LDADs). They are now registered areas of Cultural Heritage Sensitivity, but they were not always so. They were only recognised as areas of Cultural Heritage Sensitivity because the developments or projects undertaken within that location either included already registered sites within the activity area, which is rare in Greenfields developments38, or the developments were large enough to include areas of Cultural Heritage Sensitivity and as a result, the detailed site assessment that followed found the new recorded sites.

Although it cannot be definitively said these sites are where they are because of their proximity to unnamed waterways, it does demonstrate the likelihood for areas of Cultural Heritage Sensitivity to be beyond 200m of named waterways. In addition, the fact that the smaller sites are recorded only because developments or projects were undertaken in the area suggests there may be many more unrecorded sites in proximity to unnamed waterways.

Discussion question: What are your Cultural responsibilities when it comes to caring for water and waterways?

- How do Aboriginal Peoples want to interact with waters?

- What measures would empower Aboriginal Peoples to effectively pass on knowledge about their waters to future generations?

- How can Aboriginal Peoples be empowered to care for water?

Updated