Council has published Taking Control of Our Heritage, a Discussion Paper on legislative reform of the Aboriginal Heritage Act 2006. The objective of the Paper is to help everyone, Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal, Victorian and non-Victorian, have their say on the operation of the Act.

The Paper organises proposals for legislative change into themes corresponding to mechanisms and parts of the Act. Each has its own section which explains the key purpose of the proposed change and invites submissions and questions.

The primary focus of the review is the Act, however, if issues raised relate to the Aboriginal Heritage Regulations 2018 these will also be considered.

Our Cultural Heritage is best understood through demonstrating respect for Traditional Owners – our knowledge, our skills, our appreciation of our Heritage. The practicing of our Culture and Traditions makes us stronger and this strength offers all Victorians opportunities to value, understand and celebrate the unique Cultural Heritage we care for on behalf of all of us.

What do we mean by Aboriginal Cultural Heritage?

Aboriginal Cultural Heritage refers to the knowledge and lore, practices and people, objects and places that are valued, culturally meaningful and connected to identity and Country.

It shapes identity and is a lived spirituality fundamental to the wellbeing of communities through connectedness across generations. Our Cultural Heritage has been passed from the Ancestors to future generations through today’s Traditional Owners whose responsibilities are profound and lifelong.

As we reflect on thirteen years of implementation of the Aboriginal Heritage Act in Victoria, I am proud of the strength of our Cultures and the many ways Victorian Traditional Owners express and promote their Cultural Values. The health and wellbeing of our communities is underpinned by strong Culture and a strong sense of connection with it.

Together, across generations, we are the protectors of Cultural Heritage through imposed legislation and community cultural expectations. It is in our children’s lifetimes that our ambitions to be accorded the rights outlined in the United Nations Declaration of Rights for Indigenous Peoples will be realised. This Declaration enshrines the rights of our People and affirms that Indigenous Peoples are equal to all other peoples, while recognising the right of all peoples to be different, to consider themselves different, and to be respected as such.

The more people respect our unique relationship with Culture and Country, the broader the understanding they will have of Aboriginal Cultural Heritage and it being our social and cultural fabric, the greater protection is achieved.

The protection of Aboriginal Cultural Heritage in Victoria has only been necessitated since intrusion on our Country. Across Australia, the 1993 federal Native Title Act offered a statutory acknowledgement of ownership that was limited in its approach to connection to Country. In Victoria, this necessitated that key legislation was passed to ensure security for our Traditional Owners.

In 2007, the Aboriginal Heritage Act came into being, enshrining Council and its responsibilities to register Aboriginal parties to manage both Country and Cultural Heritage. Also in 2007, the United Nations General Assembly adopted the significant Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. Supporting the survival, dignity and wellbeing of Our People, the Declaration is the foundation of Council's work.

The Aboriginal Heritage Act and Declaration, together, provide some of the greatest protections for Traditional Owners in the country. However, there is still much to be done in realising a fundamentally self-determined and tangible ownership of our Culture, Heritage, History and Country.

We all have a part to play in ensuring our Peoples’ rights to self-determination, our Culture and Country. We seek the support and contribution of everyone to work with us on ensuring that the statutory protections our Peoples have for their Culture is commensurate to over 40,000 years of connection to Country.

Rodney Carter

Chairperson, Victorian Aboriginal Heritage Council

The Victorian Aboriginal Heritage Council (Council) is reviewing the Aboriginal Heritage Act 2006 (the Act). The primary focus of the review is the Act. However, if issues raised relate to the Aboriginal Heritage Regulations 2018 (the Regulations) these will also be considered.

This discussion paper is designed to help you have your say on the operation of the Act and to help you prepare a submission of any proposed legislative change(s) or comments on any of the reforms proposed in this paper.

The discussion paper organises proposals for legislative change into themes which correspond to mechanisms and parts of the Act. Each has its own section which explains the key purpose of the proposed change, and inviting submissions and questions.

How to make a submission for a proposed change

Please send any submissions through to vahc@dpc.vic.gov.au by Monday 30 November 2020.

Remember:

- Submissions do not have to deal with the whole Act.

- Only write about the parts of the Act or the themes which most interest you.

- The questions and proposed legislative changes in this discussion paper are posed as a starting point. Multiple proposals for change can be submitted on the same topic.

- The proposals contained in this paper are not intended to limit responses.

Shortened Form In Full ACHLMA

Aboriginal Cultural Heritage land management agreement Act Aboriginal Heritage Act 2006 AV Aboriginal Victoria CHA Cultural Heritage agreement CHMP Cultural Heritage permit Cultural Heritage management plan Council Victorian Aboriginal Heritage Council Declaration United Nations Declaration of Rights for Indigenous Peoples DPC Department of Premier and Cabinet DPP Department of Public Prosecutions LRRFAC Victorian Aboriginal Heritage Council Legislative Review and Regulatory Functions Advisory Committee Minister Minister for Aboriginal Affairs (Victoria) NOI Notice of intention PAHT Preliminary Aboriginal heritage test RAP Registered Aboriginal Party Register Victorian Aboriginal Heritage Register Regulations Aboriginal Heritage Regulations 2007 Secretary The Secretary to the Department of Premier and Cabinet Council has a clear goal of seeing RAPs appointed with respect to the whole of the State. While this goal is still some time off, recent amendments to the processes adopted with respect to the appointment of RAPs and the adjustment of existing RAP boundaries are likely to mean that substantial progress in the task of achieving full RAP coverage soon is possible. Whether there is full coverage or merely a significant increase from the existing 74% coverage raises the question:

Does the Act need amendment to reflect the increased coverage of RAPs and, if so, what changes are desired?

To assist in answering this question, Council has established a Legislative Review and Regulatory Functions Advisory Committee (LRRFAC) that will oversee the work of this Discussion Paper. Council has asked the Committee, and now the broader community, to do some deep thinking about what the regime around Aboriginal Cultural Heritage promotion, management and protection should be.

Information on the proposed suite of reforms

- The Aboriginal Heritage Act 2006 (the Act) came into operation on 28 May 2007. The Act was reviewed and amended last on 1 August 2016.

- The proposed suite of reforms are planned to be introduced in 2021. By this time, during the life of the current Parliament, it will be five years after the 2016 amendments to the Act and fifteen years since the Act came into existence.

- As well as to any fundamental amendments to the Act, a set of amendments in 2021 would also create the opportunity to secure any more minor and technical (but still important) amendments that RAPs may desire.

- It may be that the proposals for legislative reform stemming from this review process can not all be realised by 2021 and that a second tranche of reforms will be necessary after the next State election.

Who is involved?

- The review of the Act is being undertaken by the Victorian Aboriginal Heritage Council’s Legislative Review and Regulatory Functions Advisory Committee (LRRFAC).

- The COUNCIL will consult with key stakeholders including: the Registered Aboriginal Parties, the Federation of Victorian Traditional Owner Corporations, First Nations Legal and Research Services, Victoria’s development and land-use industry, heritage advisors, local government, and public land managers.

How will consultation be undertaken?

The LRRFAC will conduct the review of the Act in an open and transparent manner and provide opportunities for all interested stakeholders to have a say. The table below outlines the key steps and dates of the legislative reform process.

Key steps and dates

Key steps Dates Initial information presentation to RAPs at San Remo RAP Forum 26-28 November 2019 Making Change – Special RAP Forum – to discuss and develop proposed reforms 17-18 March 2020 LRRFAC Meeting 3/20 – To consider Forum outcomes for incorporation in Discussion Paper May 2020 Finalisation of Discussion Paper May 2020 Consultation with Stakeholders June-September 2020 LRRFAC Meeting - To consider stakeholder feedback October 2020 Council Meeting - Finalisation of Reform Proposal 21-23 October 2020 Taking Control of our Heritage National Conference-Release of Proposal November 2020 Considering this Discussion Paper in the context of treaty

As of February 2020, the Victorian Government has begun working towards Treaty negotiations with Aboriginal Victorians. The First Peoples’ Assembly of Victoria, established in 2019, is currently working in partnership with the Government to establish the elements required to support these future negotiations.

Any proposals for legislative changes made to the Act should be considered in the light of Treaty negotiations. Although the Treaty process is still in its early stages, Council and LRRFAC are asking all Traditional Owners to think about the implications that Treaty might have for RAPs, the Act, and the entire Aboriginal Cultural Heritage protection regime in Victoria.

Topic themes for proposed reforms

This section details some of the main points about the Act’s operation and poses a series of questions and proposed changes for consideration. The discussion paper is divided into the following themes:

Theme 1

Furthering self-determination for Registered Aboriginal Parties.

Theme 2

Increasing the autonomy of the Victorian Aboriginal Heritage Council.

Theme 3

Recognising, protecting and conserving Aboriginal Cultural Heritage.

Theme 1: Furthering self-determination for Registered Aboriginal Parties (RAPs)

Background

The COUNCIL is composed of eleven Traditional Owners. Each Council member must be an Aboriginal person who is a traditional owner, is resident in Victoria, and has relevant experience of knowledge of Aboriginal Cultural Heritage in Victoria. S 131(1) of the Act states the following:

131 Membership

The Council consists of not more than 11 members appointed by the Minister.

The operation of s 131(1) means that the Minister for Aboriginal Affairs is vested with the power to appoint all Council members.

Proposal

S 133 of the Act should be amended to allow Council to have at least five of its eleven members appointed by the RAPs themselves, rather than having the entire Council be appointed by the Minister. This would be in keeping with principles of self-determination and would enable Council to be representative of the RAP sector.

The nomination process would be in accordance with a procedure contained in a statutory instrument approved by the Minister. Election would occur via a College of RAPs, and the number of RAP-appointed nominees would be determined by a proportion which accords with RAP coverage of the State. The College would put forward their nominees to the Minister, with the Minister still having the ultimate power to decline an appointment at their discretion. However, the Minister would be unable to appoint a non-RAP elected member in their stead.

This proposal would increase RAP ownership of Cultural Heritage and strengthen the relationship between RAPs and Council. It would allow Council to become an advocate for the sector, beyond a body that just oversees the interests of RAPs. It is emphasised that this proposal is not about representation of specific RAPs, but representation of the RAP sector.

Discussion points and questions

Are the above models viable? What are other alternatives?

Who should make up the College of RAPs?

What proportion of Council members should be elected by RAPs?

- One proposal is that five members would be RAP-nominated and the other six members would not be RAP-nominated. This could be a balanced approach.

How should the nomination process work in practice?

- One proposal is that a College of RAPs would involve a meeting of RAP representatives (from all RAPs) who would propose a list of potential RAP representative nominees. This list would then go before the Minister in selecting the RAP-nominated Council members.

This could result in certain Aboriginal groups having both a RAP-nominated representative and non-RAP nominated representative(s) on Council. Is this an issue?

Background

S 148 of the Act outlines the functions of a RAP. These legislative functions mainly relate to the technical aspects of managing Cultural Heritage, such as CHMPs, Cultural Heritage permits and Cultural Heritage agreements. The only provisions in s 148 which refer to a RAP’s more general responsibilities are the following:

(a) To act as the primary source of advice and knowledge for the Minister, Secretary and Council on matters regarding Aboriginal places and objects relating to their registration area;

(fa) To provide general advice regarding Aboriginal Cultural Heritage relating to the area for which the party is registered.

Proposal

The current legislative framework needs to be expanded to encourage increased government engagement and consultation with RAPs on Cultural Heritage matters relating to both tangible and intangible heritage. In particular, the relationship between RAPs and local governments would benefit from the prescription of the specific obligations that local governments have to their relevant RAP(s).

Further, since the establishment of the first RAPs in 2007, their responsibilities and expertise have grown to a point where they are able to act as representatives of the nations in their registered area in regard to a range of matters beyond the technicalities of Cultural Heritage. The Act should be amended to reflect this, and to increase RAP’s voices as the primary source of advice to government on other Aboriginal affairs in their registration area.

These proposals seek to reclaim the rights and responsibilities of governance of Aboriginal people and would frame RAPs as the peak advisors on Aboriginal Cultural Heritage and other issues regarding Aboriginal affairs in their registration area. The actual amendments would constitute the following:

- Legislating that RAPs need to be the Minister’s primary consultant on all matters relating to Aboriginal Cultural Heritage in the registration area.

- Legislating that local governments need to build a close relationship with their relevant RAP(s) and that RAPs need to be their primary consultant on all matters relating to Aboriginal Cultural Heritage in the local government area.

- Legislating that both State and local government should be directed to consult with RAPs on matters of intangible heritage as well as tangible heritage.

- Legislating that both State and local government should be directed to consult with RAPs on matters relating to other Aboriginal affairs in their registration area beyond Aboriginal Cultural Heritage.

Discussion points and questions

Should RAPs be prescribed as the primary source of advocacy and advice to government on matters relating to Aboriginal affairs that are outside the ambit of Aboriginal Cultural Heritage?If so, what should constitute these matters? Some proposed matters are:

- health

- housing

- social services

What other legislative functions of a RAP should be included in s 148?

Could this proposal cause friction between RAPs and other organisations who are servicing Aboriginal communities?

Would this proposal interfere with each individual RAP’s choice to decide on how and when they wish to communicate with local government?

How would this proposal interact with RAPs who have agreements under the Traditional Owner Settlement Act 2010, which already provides established frameworks for engagement with local, state and federal governments?

Background

S 154A of the Act stipulates the following:

154A Conditions of Registration

The Council may impose conditions on the registration of a registered Aboriginal party at any time.

As such, Council has the power to impose conditions on the registration of any RAP. However, this provision is only in regard to existing RAPs. The current legislative framework does not allow newly appointed RAPs to have conditions set on their registration immediately upon appointment.

Proposal

The Act should be amended to enable Council to approve RAP applications subject to conditions. This would allow groups that are potentially unable to carry out all their functions as a RAP at the time of application to still have their registration as RAP approved. Additionally, it would stagger the commencement dates of the new RAPs’ obligations so that they would not immediately be flooded with all RAP responsibilities upon registration.

For example, if a RAP was appointed over a small area that had a disproportionately high number of activities requiring CHMPs, its appointment could be subject to the condition that for the first six months following the appointment, it does not have the power to approve CHMPs over a certain zone of its registration area. This would enable the RAP to spend that period establishing itself and obtaining the funding and resources to be able to properly approve CHMPs over the entirety of its registration area.

This amendment would provide great assistance to new RAPs in their early stages of development. It would also make it more efficient for Traditional Owner groups to apply for and obtain RAP status. In turn, this would encourage inclusivity of more groups and would increase the rate at which Victoria achieves full RAP coverage.

Discussion points and questions

Does this proposal potentially limit the functions of new RAPs to an extent that it outweighs the benefits?

What types of conditions would be beneficial for new RAPs?

Is this amendment necessary considering that there are already procedures and policies in place that make it easier for newly appointed RAPs to carry out their functions? These procedures and policies include:

- The power under s 55(2) of the Act for RAPs to decide within 14 days whether or not to evaluate a CHMP, in which case it defers to the Secretary upon their refusal.

- The development of CHMP evaluation checklists and CHP application forms.

Background

Currently, the responsibility of preparing a CHMP lies solely with Heritage Advisors. This is stated in s 58 of the Act:

Engagement of heritage advisor

The sponsor of a Cultural Heritage management plan must engage a heritage advisor to assist in the preparation of the plan.

This gives Heritage Advisors control over the preparation of CHMPs. Meanwhile, the role of RAPs in the CHMP process is to consult with the Heritage Advisor and the Sponsor throughout the preparation of the plan. Then, RAPs have the authority to approve or refuse the CHMP under s 63 of the Act.

Proposal

S 58 should be amended to allow Sponsors to engage RAPs to assist in the preparation of CHMPs that are in relation to activities within their registration areas, as an alternative to Heritage Advisors. This would allow RAPs to act as the primary consultant of the Sponsor throughout the CHMP process and would empower Traditional Owners with the protection and management of their own Cultural Heritage. It would also strengthen the relationship between Traditional Owners and Sponsors by encouraging them to have more direct interaction during the preparation of a CHMP. Furthermore, it would mitigate the increasing pressure on the Heritage Advisor industry by directly transferring workloads from Heritage Advisors to RAPs. In turn, this would enable Heritage Advisors to produce higher quality CHMPs with higher rates of immediate approval from RAPs.

This proposal comes with the inherent issue that there is a potential conflict that arises when RAPs have the dual role of preparing a CHMP and acting as the approval body for that same CHMP. However, provided that a RAP is not both the proponent of a CHMP and the approver of the CHMP, this conflict is potentially illusory.

By comparison, in the Northern Territory the consultation and approval of the CHMP equivalent is done within the one government agency. The Aboriginal Areas Protection Authority (“AAPA”) is a statutory body mainly composed of Aboriginal custodians of sacred sites that is commissioned by the Northern Territory Aboriginal Sacred Sites Act 1984 (“NTASSA”). If a person proposes to use or carry out work on land in the vicinity of sacred sites, they are obliged to apply to the AAPA for an “Authority Certificate” under s 19B of NTASSA. The AAPA then must consider a range of relevant issues and must decide whether to issue an Authority Certificate under s 22. Therefore, Traditional Owners are positioned as both the primary consultants and preparers of the Authority Certificate application, and the primary approval body. This is a viable model that could be followed in Victoria.

As long as the Act maintains the two-party relationship between Sponsors as proponents of the CHMP, and RAPs as the preparers and approval bodies of the CHMP, there is no reason to suggest that the role of the third-party Heritage Advisor could not be omitted in certain circumstances.

Discussion points and questions

Could a RAP realistically be positioned as the preparer and the approver of a CHMP, or is the risk of conflict too great?

The way that RAPs could be structured in accordance with this proposal is to have both a research arm (to conduct CHMPs) and a regulatory arm (to evaluate CHMPs).

If this amendment was put in place, RAPs could potentially work on each other’s country in a RAP peer review process.

- Would resourcing this proposal be too difficult for RAPs?

- What would this proposal mean for disputes that arise between Sponsors and RAPs?

- Is this proposal better suited to only include work over Crown land or public lands where the Sponsor is the State?

Background

Under s 63(4) of the Act, a RAP may only refuse to approve a CHMP on substantive terms if it is not satisfied that the plan adequately addresses the matters set out in s 61. S 61 sets out matters to be considered in assessing CHMPs, including the following:

(a) Whether the activity will be conducted in a way that avoids harm to Aboriginal Cultural Heritage; and

(b) If it does not appear to be possible to conduct the activity in a way that avoids harm to Aboriginal Cultural Heritage, whether the activity will be conducted in a way that minimises harm to Aboriginal Cultural Heritage.

The application of s 61(b) means that Sponsors have the power to argue that an activity must still go ahead despite the threat of harm to Aboriginal Cultural Heritage. This is because the activity is still arguably being conducted in a way that minimises that harm. Thus, the RAP’s position in the approval process is less about protecting Aboriginal Cultural Heritage and becomes something in the way of managing damage to Cultural Heritage. RAPs are often placed in a difficult negotiating position, having to approve CHMPs that still cause harm to Cultural Heritage.

Proposal

The Act should be amended to allow RAPs a veto power over CHMPs that threaten harm to Aboriginal Cultural Heritage. This would be in accordance with s 1(b) of the Act, which states that a purpose of the legislation is to empower Traditional Owners as protectors of their Cultural Heritage. It would also accord with Article 31 of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, which states that Indigenous peoples have the right to maintain, control, protect and develop their Cultural Heritage.

Victoria would not be the first jurisdiction in Australia to introduce a provision of this kind. S 10(f) of NTASSA gives the AAPA the function to refuse to issue an Authority Certificate it believes that there is a threat of harm to sites of Cultural Heritage significance. Developers are then unable to carry out activities without this Authority Certificate. They are also unable to apply again for that same Authority Certificate, except with the permission in writing of the Minister. Allowing RAPs in Victoria this same authority would enable them more control over the management of their Cultural Heritage.

Discussion points and questions

Is a veto power for CHMPs feasible?

Should the veto power be at the approval stage, or should it be relevant to the preliminary stages of the CHMP preparation process?

What form could a veto power take?

If a site was found during a CHMP assessment to be of Local, State, National or International significance, could this provide the foundation for veto powers?

Theme 2: Increasing the autonomy of the Victorian Aboriginal Heritage Council

Background

S 143(1)(b) of the Act states that one of the functions of the Secretary is to establish and maintain the Victorian Aboriginal Heritage Register. This means that powers over the Registration of Aboriginal heritage lie with employees of AV, and not with Traditional Owners. Registry staff’s views on what is appropriate for Registration can often conflict with those of both Traditional Owners and Heritage Advisors, meaning that what appears on the Register is not always representative of the views of Traditional Owners.

Proposal

The Act should be amended to transfer responsibility of the VAHR (including Registration of both tangible and intangible heritage) to Council.

S 1(b) states that one of the Act’s purposes is to empower Traditional Owners as protectors of their Cultural Heritage on behalf of Aboriginal people. Transferring the responsibility of maintaining the Register to Council would allow Traditional Owners to oversee the Registration of Aboriginal Cultural Heritage, empowering them with the management of their heritage and therefore aligning with the purposes of the Act.

S 144A(a) states that a main purpose of the Register is for Victorian Traditional Owners to store information about their Cultural Heritage. It follows on from this notion that Victorian Traditional Owners should be the group that actually stores the information on the Register. As Council is composed solely of Traditional Owners, they are the most suitable authority to oversee the storing of this information.

In practice, the transfer of responsibility of the Register would result in the current staff who monitor and maintain the Register having their operations transferred to the Office of the COUNCIL. There, they would report to and be overseen by Council to ensure that Traditional Owners had oversight over the Registration process and the ongoing maintenance of the Register. This proposal would not change Registry’s main functions, which is to act as a repository of information.

Discussion points and questions

How should this transfer of responsibility work in practice? Is the above proposal workable?

What specific aspects of Registration need to be considered when discussing the transfer of the Register’s operations from AV to Council?

Note that s 145, s 146, s 146A, s 147 and s 147A would also need to be amended to take out Secretary functions.

If this proposal was accepted, Council would create standards and policies relating to the Register by listening to the ‘on ground’ experiences of RAPs and Traditional Owners.

Background

Part 8 of the Act outlines the procedures to be followed when disputes arise regarding Aboriginal Cultural Heritage. These procedures mainly involve applying to the Victorian Civil and Administrative Tribunal for review of a decision made by a RAP, the Secretary, the Minister or another approval body. Division 1 deals with disputes regarding CHMPs, Division 2 deals with disputes regarding Cultural Heritage permits, and Division 3 deals with disputes regarding protection declaration decisions.

Division 1 is the only one of these three Divisions to provide procedures for alternative dispute resolution (“ADR”). S 111 outlines exactly which disputes can be subject to ADR under Division 1:

111 Meaning of Dispute

In this Subdivision, dispute means a dispute between 2 or more registered Aboriginal parties, or between the sponsor of a Cultural Heritage management plan and a registered Aboriginal party, arising in relation to the evaluation of a party for which approval is sought under section 62, but does not include a dispute arising in relation to the evaluation of a plan for which approval is sought under section 65 or 66.

The disputes described in s 111 are therefore the only type of disputes that are eligible for ADR. The specific process for ADR under Division 1 is outlined in s 113(2):

(2) The Chairperson may … arrange for the dispute to be the subject of –

(a) mediation by a mediator; or

(b) another appropriate form of alternative dispute resolution by a suitably qualified person.

Therefore, ADR under Division 1 can only be facilitated through mediation or another form of ADR by this external arrangement.

Proposal

Part 8 should be amended to expand ADR as the primary mechanism for the resolution of any dispute arising under the Act. This would mean that parties have more options for dispute resolution before applying to VCAT or going to court, both of which can be costly, time-consuming and inefficient. It would also be in line with Council’s newly introduced “Complaints Against RAPs” and “Imposition of Conditions” Policies.

These changes can be made in the following 3 ways:

- The amendments should expand the types of disputes that are eligible for ADR under the Act beyond the one type that is outlined in s 111. For example, the meaning could be expanded to include disputes regarding Cultural Heritage permits and disputes regarding protection declaration decisions. Ideally, it would include all disputes that arise under the Act.

- The amendments should expand the parties that are eligible for ADR under the Act beyond RAPs and Sponsors. For example, ADR could be arranged for disputes between RAPs and other non-RAP Traditional Owner groups.

- The role of Council in the ADR process should be expanded beyond arranging the dispute to be the subject of external ADR. Council should be the initial body that facilitates disputes arising under the Act, as an alternative to external mediators. The facilitation would likely occur through the Office of the Council. This proposal would be in line with Council’s statutory function “to manage, oversee and supervise the operations of registered Aboriginal Parties” set out in s 132(2)(ch) of the Act. It would also be in line with the new “Complaints Against RAPs” and “Imposition of Conditions” Policies, which outline a more structured process for the way that Council deals with complaints and disputes relating to RAPs. If the parties did not wish for Council or the Office of the Council to facilitate the mediation of their dispute, then they could elect for external mediators to facilitate it.

These amendments would ensure that there are more formal options and processes that are available to more parties in regard to disputes that arise under the Act. It would also give Council more authority in the dispute resolution process, therefore increasing their autonomy and status as the peak body representing Traditional Owners in Victoria.

Discussion points and questions

Is it correct for Council, or the Office of the Council, to have the role as a mediating body in these dispute processes?

If not, then what other authority could have this role? Or should the role be eliminated as a possibility altogether?

Which parties should be eligible for ADR under the Act?

Which parties should be liable for the costs of paying for these dispute resolution processes?

Background

Ss 186(1) and 188(2) of the Act state the following:

186 Who may prosecute?

(1) … proceedings for an offence against this Act may only be taken by the Secretary or a police officer.

188 Delegation(2) The Secretary may, in writing, delegate any of his or her powers, functions, or duties under this Act, other than this power of delegation, to a person employed in the Department.

Read together, these provisions mean that the power to prosecute a person for an offence against the Act may only be taken by an employee of DPC, as delegated to by the Secretary. As it stands, these rights and responsibilities of prosecution lie with AV. Furthermore, DPP has the ultimate power to decide whether an offence warrants a court hearing. One of DPP’s assessments in making this decision is whether prosecution is ‘in the public interest.’ Cases are often not progressed because DPP deems them to not be ‘in the public interest.’

Proposal

The rights and responsibilities of prosecution should be moved to the COUNCIL so that it can prosecute as a statutory authority on its own behalf. Other statutory authorities, such as the Environmental Protection Agency and the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, have prosecution powers. Offences against the Act result in harm to Aboriginal Cultural Heritage, which is harm against the interests of RAPs and Traditional Owners. To award increased powers to Traditional Owners in the oversight and management of prosecuting and actioning regulatory responses to offences would be in keeping with principles of self-determination, and specifically with the Act’s purpose of empowering Traditional Owners as protectors of their Cultural Heritage.

To this end, it is further proposed that: Aboriginal Heritage Officers (AHOs) and Authorised Officers (AOs) should be empowered to issue infringement notices in relation to minor offences. Infringement notices enable offences to be dealt outside of court. Provision of powers to AHOs and AOs to issue such notices would relieve some of the workload from the State and transferring the powers to Council could also ensure that there is increased action taken against offences. AV has often taken a cautious approach to prosecution. RAPs often expend large amounts of time and resources on gathering evidence for potential offences yet are not closely involved in AV’s investigation process. However, if the powers were moved to Council and increased powers were provided to AOs and AHOs, breaches of the act could be acted upon more often and more thoroughly. In turn, this would have a denunciating and deterrent effect to encourage increased compliance with the Act.

Empowering the COUNCIL to prosecute offences could also build stronger relationships between RAPs and Council. The prospect of Council’s full engagement with RAPs throughout the investigation and prosecution procedures would provide for both increased transparency in the process and stronger links between the parties.

Discussion points and questions

Should the power to prosecute sit with the Council?

Which offences under the Act would be appropriate to issue an infringement notice as a penalty?

Should RAPs be given powers to issue infringement notices?

What are other issues with the current prosecution process that could be amended?

Background

S 138(3)(a) of the Act states the following:

138 Election of Chairperson and Deputy Chairperson

(3) The Chairperson and Deputy Chairperson –

(a) hold office for one year; and

(b) are each eligible for re-election for two further terms of one year.

Both the Chairperson and the Deputy Chairperson are therefore only eligible for terms of one year at a time.

Proposal

The Act should be amended to extend election terms to two years. The current system of one-year leadership terms is unworkable. Longer terms will allow the Chairperson and Deputy Chairperson to provide stability of leadership, properly develop relationships, and effectively represent the Traditional Owner sector.

Flowing from the above proposal, the Chairperson and Deputy Chairperson should only be eligible for one further term of re-election. This will mean that the total amount of time that a Council member could hold either of these offices is four years.

Discussion points and questions

What are appropriate term lengths for the Chairperson and Deputy Chairperson?

How many times should the Chairperson and Deputy Chairperson be eligible for re-election?

Background

Currently, the Office of the COUNCIL is a branch of AV. Therefore, all its staff members are employed through DPC.

Proposal

The Act should be amended to allow Council to employ its own staff. This would be in keeping with principles of self-determination and would provide greater autonomy to Council as an independent statutory authority.

Discussion points and questions

Should Council be permitted the ability to employ its own staff?

Background

Under s 143 of the Act, the Secretary’s functions include the following:

143 Functions of the Secretary

(a) to take whatever measures are reasonably practicable for the protection of Aboriginal Cultural Heritage;

(b) to establish and maintain the Victorian Aboriginal Heritage Register;

(c) to grant Cultural Heritage permits;

(d) to approve Cultural Heritage management plans in the circumstances set out in section 65;

(e) to develop, revise and distribute guidelines, forms and other material relating to the protection of Aboriginal Cultural Heritage and the administration of this Act;

(f) to publish, on advice from the Council, appropriate standards and guidelines for the payment of fees to registered Aboriginal parties for doing anything referred to in section 60;

(g) to publish standards for the investigation and documentation of Aboriginal Cultural Heritage in Victoria;

(h) to manage the enforcement of this Act;

(i) to collect and maintain records relating to the use by authorised officers of their powers under this Act;

(j) to facilitate research into the Aboriginal Cultural Heritage of Victoria;

(k) to promote public awareness and understanding of Aboriginal Cultural Heritage in Victoria;

(l) to maintain a map of Victoria which shows each area in respect of which an Aboriginal party is registered under Part 10, and to make the map freely available for inspection by the public;

(m) to maintain a list of all Aboriginal parties registered under Part 10 that includes contact details for the parties, and to make the list freely available for inspection by the public;

(n) to carry out any other function conferred on the Secretary by or under this Act;

(o) to consider applications for the registration of Aboriginal intangible heritage and make determinations regarding sensitive Aboriginal heritage information;

These functions are all carried out by AV in the name of the Secretary.

Proposal

Some of the above responsibilities, as well as others outlined in other parts of the Act, should be transferred from the Secretary to the COUNCIL. The transfer of some of these functions has already been considered in other proposals in this paper (such as Proposals Six and Eight).

For example, as stated above at Page 16, one of Council’s statutory functions is “to manage, oversee and supervise the operations of registered Aboriginal Parties” set out in s 132(2)(ch) of the Act. However, the majority of RAP support functions currently sit with AV, rather than Council. If the Act was amended to encourage more RAP support functions to sit with Council, then the relationship between RAPs and Council would be strengthened. Furthermore, it would allow RAPs more direct support from Traditional Owners.

Discussion points and questions

What functions of the Secretary should be transferred to Council?

Looking at section 143 of the Act, are there any functions of the Secretary that should be transferred directly to RAPs?

Should RAPs keep their own Registers?

Theme 3: Recognising, protecting and conserving Aboriginal Cultural Heritage

Background

S 58 of the Act gives specific responsibility over the preparation of a CHMP to Heritage Advisors. During the preparation of a CHMP, they are expected to fulfil a range of obligations, including consulting with Traditional Owner Groups and RAPs, conducting Cultural Heritage assessment of an activity area in compliance with the Act, and preparing the final CHMP in accordance with the prescribed conditions. Heritage Advisors therefore have a key role in the protection and management of Aboriginal Cultural Heritage in Victoria.

Sponsors of development activities engage and pay Heritage Advisors to prepare CHMPs. Whilst Sponsors can be held liable for causing unauthorised harm to Aboriginal Cultural Heritage under the Act, there are no consequences for misconduct on the part of the Heritage Advisor. This makes them unaccountable for failure to engage in proper consultation with Traditional Owners, or for drafting poor or incomplete CHMPs. Furthermore, their economic relationship with the Sponsor gives them more incentive to act in the Sponsor’s interests, rather than the interests of Traditional Owners.

Proposal

The Act should be amended to create a regulation system for Heritage Advisors. Regulation would include a formal registration system, a binding code of conduct, a formal complaints process and the enforcement of sanctions. This would protect Traditional Owners and the public from poor practices. It would also benefit Sponsors and Heritage Advisors as it would provide them with stronger relationships with Traditional Owners and better heritage management outcomes.

Preceding the implementation of the relevant amendments to the Act would be the introduction of non-binding guidelines holding Heritage Advisors to a standard of conduct. These guidelines would be produced by Council under their statutory function to publish policy guidelines consistent with the functions of the Council as per

s 132(2)(ck) of the Act. This would assist in establishing a foundation for the introduction of the amendments in 2021.

The onus to produce satisfactory CHMPs that are the result of thorough Cultural Heritage assessments and proper engagement with Traditional Owners needs to be on Heritage Advisors themselves. Implementing a system where Heritage Advisors will be held accountable for their actions will help to create an industry standard that lifts quality of work and builds stronger relationships for all parties involved in the CHMP process.

Discussion points and questions

What other elements should a regulation system for Heritage Advisors include?

What rules should be listed in the Heritage Advisors code of conduct?

What pre-existing body should act as a regulator for Heritage Advisors? Should it be Council, or a different body?

What sanctions against Heritage Advisors should be available?

Background

S 59 of the Act sets out the obligations between a Sponsor and a RAP during the CHMP process.

59 Obligations of sponsor and registered Aboriginal party

(1) This section applies if a registered Aboriginal party gives notice under section 55 of its intention to evaluate a Cultural Heritage management plan.

(2) The sponsor must make reasonable efforts to consult with the registered Aboriginal party before beginning the assessment and during the preparation of the plan.

(3) The registered Aboriginal party must use reasonable efforts to co-operate with the sponsor in the preparation of the plan.

Although Sponsors are obliged to ‘make reasonable efforts to consult’, there is no binding obligation to consult with a RAP during the process. This is problematic. For example, under the current regime, Sponsors often engage Heritage Advisors and begin preliminary discussions regarding a CHMP before a RAP has even been provided with the Sponsor’s Notice of Intention to prepare the plan. This means that preparations of a CHMP begin to occur before a RAP has knowledge of the activity. It encourages the development of a relationship between the Sponsors and Heritage Advisors that omits the interests of Traditional Owners.

Proposal

The Act should be amended to require Sponsors to consult with RAPs from the outset of the CHMP process. This will ensure that RAPs are informed and have a say in activities regarding the assessment of Aboriginal Cultural Heritage values. If it was stated in the Act that prospective Sponsors had to consult with Traditional Owners before engaging a Heritage Advisor, then both parties would be able to create a stronger relationship throughout the consultation process.

Creating a strategy for greater consultation between all parties would ensure enhanced accountability of Sponsors and Heritage Advisors. Additionally, Sponsors who establish a relationship with the RAP of the area of the area in which they wish to undertake an activity will be able to make an informed decision when engaging a HA.

Discussion points and questions

Do RAP’s see an advantage in being given the opportunity to forge a relationship with prospective Sponsors?

Background

Under the Act, Authorised Officers (“AOs”) and Aboriginal Heritage Officers (“AHOs”) are appointed by the Minister to carry out the Act’s enforcement functions. Those functions include monitoring compliance with the Act, investigating suspected offences against the Act, and issuing and delivering stop orders under Part 6 of the Act. Under s 166 of the Act, both AOs and AHOs have a general power to enter land or premises to carry out these functions.

S 166(2) specifically stipulates the following:

166 General power to enter land or premises

(2) An authorised officer or Aboriginal heritage officer must not enter any land or premises under this section –

(a) without the consent of the occupier of the land or premises; and

(b) unless the occupier –

(i) is present; or

(ii) has consented in writing to the authorised officer or Aboriginal heritage officer entering the land or premises without the occupier being present.

S 167 then sets out the specific procedures for obtaining consent of the occupier.

Proposal

The Act should be amended to allow AOs and AHOs to enter land or premises without the consent of the occupier.

The current legislation restricts AOs’ and AHOs’ powers to the point where they are inhibited from carrying out their functions. In the likely event that an individual who is suspected of an offence against the Act does not give an Officer consent to enter their premises, the Officer is stopped from carrying out their duty to protect Aboriginal Cultural Heritage.

Although this amendment may seem like a curtailment of the occupier’s rights, it is necessary for striking the balance between those rights and the rights of Traditional Owners under the Act. Namely, the rights to the protection and management of their own Cultural Heritage.

Discussion points and questions

Encroaching on occupiers’ rights, particularly on residential premises, is a significantly serious proposal. Is this a workable amendment?

What alternative proposals could enable AOs and AHOs to have a greater power to enter premises when there is a potential threat of harm to Aboriginal Cultural Heritage, and yet still uphold occupiers’ rights of consent?

Background

S 187 of the Act sets out evidentiary rules which apply for proceedings for offences under the Act. Specifically, s 187(2) details that certificates signed by certain parties can act as evidence for the facts stated in that certificate. For example, s 187(2)(e) states the following:

(2) In any proceedings for an offence against this Act –

(e) a certificate signed by the Chief Executive Officer of the Museums Board to the effect that an object referred to in the certificate is an Aboriginal object is evidence of that fact.

It is also noted that there is currently no mechanism under the Act to determine whether an Aboriginal Object is Secret or Sacred.

Proposal

S 187(2) should be amended to include an additional provision similar to s 187(2)(e) that enables certificates signed by the Victorian Aboriginal Heritage Council to the effect that an object referred to in the certificate is an Aboriginal Object or Secret or Sacred Object to be evidence of that fact.

This would mean that when Secret or Sacred Objects, or Aboriginal Objects in general, are necessary as evidence in proceedings for offences against the Act, Council would have the authority to deem the Objects as such.

Discussion points and questions

Noting that a guiding principle for Council is that Traditional Owners of the lands in which certain objects originate should make the call. How should Council best work with Traditional Owners in non-RAP areas where there may be multiple interests?

Should Council create a Sub-Committee that could act as a mechanism to determine specific matters in relation to Secret or Sacred Objects?

Background

Currently, all offences capable of being committed under the Act are criminal offences.

Proposal

The Act should be amended to introduce liability for civil damages for every offence. This will result in greater rates of compliance with the Act for the following key reasons:

- Introducing civil damages will urge high rates of compliance with the Act amongst Corporations. Most Corporations are often driven by the main intent of maximising profits. Therefore, the possibility of criminal prosecution is less of a threat than that of civil liability and the ensuing damages.

- The Department of Public Prosecutions has the ultimate discretion to prosecute criminal offences under the Act. That means that many suspected offences are not prosecuted. For civil offences, this discretion would be diverted away from the Department of Public Prosecutions. This would potentially result in more offenders being held liable.

- For civil offences, the relevant threshold for establishing liability is if a party is found to have committed an offence on the ‘balance of probabilities.’ This is lower than the threshold for criminal offences, which dictates that it must be ‘beyond reasonable doubt’ that a party offended. Introducing civil damages provisions would therefore result in a lower standard of proof for parties being held liable for offences against the Act.

Discussion points and questions

Should civil damages be introduced for every offence?

Background

S 26 of the Regulations states that a waterway or land within 200 metres of a waterway is an area of Cultural Heritage sensitivity, unless it has been subject to significant ground disturbance. S 5 of the Regulations defines ‘waterway’ as the following:

Waterway means –

(a) a river, creek, stream or watercourse the name of which is registered under the Geographic Place Names Act 1998 and includes any artificially manipulated sections; or

(b) a natural channel the name of which is registered under the Geographic Place Names Act 1998 and includes any artificially manipulated sections in which water regularly flows, whether or not the flow is continuous; or

(c) a lake, lagoon, swamp or marsh, being –

(i) a natural collection of water (other than water collected and contained in a private dam or a natural depression on private land) into or through or out of which a current that forms the whole or part of the flow of a river, creek, stream or watercourse passes, whether or not the flow is continuous; or

(ii) a collection of water (other than water collected and contained in a private dam or a natural depression on private land) that the Governor in Council declares under section 4(1) of the Water Act 1989 to be a lake, lagoon, swamp or marsh.

Ss (d) and (e) then go on to provide further specifications. This definition means that many waterways in Victoria that remain ‘unnamed’ are not defined as areas of Cultural Heritage sensitivity and are therefore not protected under the Act. This has resulted in substantial harm to Aboriginal Cultural Heritage due to activities being permitted in and around unnamed waterways.

Proposal 1

The Act should be amended to expand the definition of waterway to include all courses of water in Victoria, regardless of whether they are named or unnamed, whether they are current or prior, whether they are diverted or original, or whether they are permanent or seasonal. All references to the Geographic Place Names Act 1998 should be removed. This would provide proper protection to all areas of Cultural Heritage sensitivity that exist in and around waterways in the State.

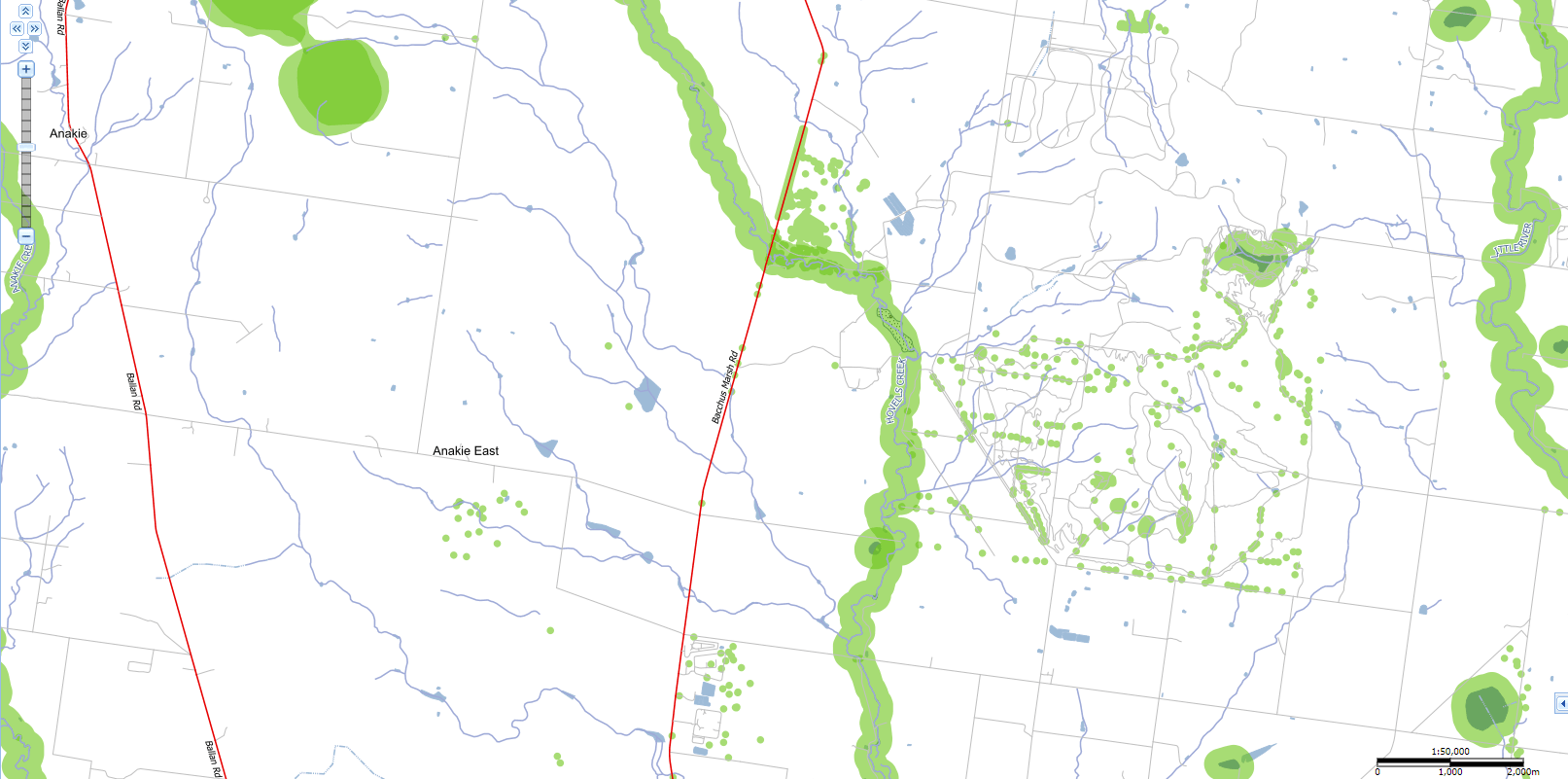

Changing this definition would also reflect the fact that watercourses change substantially in size, flow and direction over long periods of time. Many waterways that were formally significant have shrunk in size or have dried up and changed course. They are therefore often unnamed, even though they can still be areas of Cultural Heritage sensitivity. This is evident in the below image.

As can be seen above, there are numerous mapped waterways that are not areas of Cultural Heritage. There are also many recorded sites that sit outside of areas of Cultural Heritage sensitivity but are in close proximity to unnamed waterways. Although it cannot be definitively said these sites are where they are because of their proximity to unnamed waterways, it does demonstrate the likelihood for areas Cultural Heritage sensitivity to be beyond 200m of named waterways.

The most practicable avenue for this objective is to extend the sensitivity mapping in ACHRIS to include all waterways that are viewable on the system.

Proposal 2

Alternatively, RAPs should be afforded the power of becoming Victorian naming authorities over waterways in their registration area. This would allow RAPs to have control over which waterways fit within the scope of the Act and can be defined as areas of Cultural Heritage sensitivity. This would also combat an issue that comes with Proposal 1: affording all currently unnamed waterways protection under the Act could be problematic, as they cannot always be specifically and consistently identified.

However, Proposal 2 comes with various potential issues of its own. For example, there are an immense number of unnamed waterways in Victoria: placing the responsibility on a RAP to name every waterway in its registration area that it considers to be an area of cultural sensitivity could be a heavy burden. Further, if a RAP named a waterway midway through a project that was occurring within 200 metres of that waterway, all work that had been completed prior could be deemed to have harmed Cultural Heritage. These are issues that need to be considered when debating the efficacy of these Proposals.

Discussion points and questions

What other issues arise with either of these Proposals?

In what other ways could the ‘unnamed waterways’ issue be resolved?

Background

S 7 of the Regulations states that CHMPs are required for an activity if all or part of the activity area is an area of Cultural Heritage sensitivity, and if all or part of the activity is a high impact activity. The Regulations also state that various places are not areas of Cultural Heritage sensitivity if they have been subject to significant ground disturbance (“SGD”). The definition of SGD therefore has significant implications for when CHMPs are and are not required for an activity.

SGD is defined in s 5 of the Regulations:

significant ground disturbance means disturbance of –

(a) the topsoil or surface rock layer of the ground; or

(b) a waterway –

by machinery in the course of grading, excavating, digging, dredging or deep ripping, but does not include ploughing other than deep ripping.The definition being limited to ‘topsoil’ is inadequate when used to define an area of Cultural Heritage sensitivity. Thousands of test pits have shown that artefact bearing soil can be at depths far greater than what is recorded as topsoil. That means that those parts of the stratigraphy are not sufficiently protected by the current definition.

Another significant issue with the current framework is that places and objects with Cultural Heritage sensitivity do not lose their significance just because they have been disturbed. That means that CHMPs are not mandatory for activities that are in fact often harming Cultural Heritage. For regions where there are large numbers of post-contact items that are of Cultural Heritage significance, this is a particularly pertinent concern.

Comment from RAPs on this area has indicated that In the early period of the Act ‘significant ground disturbance’ caused considerable confusion and debate – a practice note had to be written to explain how to assess SGD. While more information came forth from later CHMP investigations that provided clearer evidence to sub surface archaeological deposits across landscapes, the depth of deposits still cannot be determined using the current methodology until complex testing is undertaken.Comment from RAPs has also indicated that another important consideration is the establishment of stratigraphy on landforms. Currently Aboriginal Victoria (Heritage Services) requires that when undertaking a complex assessment first the stratigraphy is established (i.e. undertake a 1 metre X 1 metre excavation pit). RAPs commented that this approach is inadequate – the pit may be placed where no sub-surface archaeological deposits exist A better method the RAPs suggest would be using shovel test pits which will provide a much more comprehensive understanding of:

- the stratigraphy across the activity area

- establish if Cultural Heritage is present

- define extents of Cultural Heritage

- guide where salvage should occur

The RAPs have suggested that the Regulations should be amended to deal with these issues. And also that the definition of “high impact” may require consideration if the SGD definition is amended.

Proposal

The use and definition of SGD needs to be reviewed to ensure that places are only classified as not being areas of Cultural Heritage sensitivity when it is appropriate. This will ensure protection of Aboriginal Cultural Heritage and align with the fact that objects and places do not necessarily lose Cultural Heritage significance once they have been disturbed.

However, simply changing the definition of SGD is problematic. This is because the Regulations also employ the current definition of SGD to assist in determining whether an activity is ‘high impact’ or not. Various provisions state that certain activities are high impact if they do result in SGD. As above, a CHMP will only be required for an activity if all or part of that activity is high impact. Any change to the definition of SGD needs to take this into account.

A solution to this issue is to replace the use of SGD with a different term in two Sections of the Regulations. The use of SGD would remain in Division 5 Part 2 of the Regulations. An addition to the definition of the new term in relation to waterways should also be inserted.

Replace SGD with new term and definition in specific Sections

In Division 3 and s 44(3) of Division 4 in Part 2 of the Regulations, the use of the term SGD needs to be replaced with ‘subject to complete removal of all culturally relevant stratigraphy’.

The definition of ‘culturally relevant stratigraphy’ should be inserted in s 5 as ‘Topsoil, subsoil and loose, weathered basal rock’.

For instance, the amendment would read as thus;

40 Dunes

(1) Subject to subregulation (2), a dune or a source

bordering dune is an area of Cultural Heritage

sensitivity.

(2) If part of a dune or part of a source bordering dune has been subject to complete removal of culturally relevant stratigraphy, that part is not an area of Cultural Heritage sensitivity.

etc ...

Retain use of SGD in Division 5 Part 2

In Division 5 of Part 2, the use of the term SGD for defining high impact activities should remain. The current definition of SGD is suitable for this purpose.

Additional definition of new term for waterways

In s 26(2) of Division 3 in Part 2, the use of SGD for the purposes of waterways should be replaced with the new term with the additional definition ‘subject to complete removal of culturally relevant stratigraphy and all alluvium and colluvium considered to be younger than 100 000 yrs BP.’

Discussion points and questions

How to ensure areas of Cultural Heritage sensitivity that have experienced a degree of disturbance, but still may contain Cultural Heritage, are not exempt from the CHMP process whilst retaining the existing threshold for defining a high impact activity.

It is noted that the definition of ‘high impact’ will likely also need to be amended if the definition of SGD is amended.

Background

Due Diligence Assessments are advisory assessments taken by Heritage Advisors that quantify the risk about a defined situation or recognisable hazard in relation to Cultural Heritage. They are not regulated under the Act. Due Diligences are intended to establish a Sponsor’s legislative requirements for a proposed activity, such as whether a CHMP is required for that activity. However, they are usually made without consultation of the relevant RAP. This means that RAPs can often be completely unaware that a Due Diligence has been undertaken for a proposed activity.

S 49B of the Act also provides for PAHTs, which are a formalised mechanism for determining whether a proposed activity requires the preparation of a CHMP:

49B Application for the certification of preliminary Aboriginal heritage test

(1) A person proposing an activity may prepare a preliminary Aboriginal heritage test for the purposes of determining whether the proposed activity requires the person to prepare a Cultural Heritage management plan.

Currently, Heritage Advisors are not required to consult with RAPs in the preparation of a PAHT.

Proposal

Currently, if a planning application does not trigger a CHMP, an LGA may request the Sponsor engage a Heritage Advisor to undertake a Due Diligence assessment or a Preliminary Aboriginal Heritage Test (PAHT), before a planning application is approved. These processes do not require the employed Heritage Advisor consult with relevant Traditional Owner groups or RAPs.

It is proposed the Act be amended to require all building and construction related planning applications include Traditional Owner consultation. If a planning application does not trigger a CHMP, then a PAHT must be undertaken. The Act would also be amended to require Heritage Advisors to seek participation and input from RAPs in the preparation of the PAHT. This would not only offer RAPs an opportunity to provide input and guidance as to the whether an activity requires a CHMP, but would also offer an opportunity for RAPs to draft conditions for inclusion within the PAHT. These conditions could include provisions for RAPs to undertake compliance inspections they may deem necessary during the proposed activity.

These amendments would ensure that the Act provides a comprehensive system of Cultural Heritage protection throughout all the stages of any proposed activity.

Discussion Points and Questions

Is a Due Diligence still an acceptable management tool for LGAs to make decisions on matters of Cultural Heritage?

What would be a RAP’s desired degree of consultation in the preparation of a PAHT?

Would RAPs accept that there may be a different fee structure to CHMP work compared with work undertaken in the preparation of a PAHT? I.e., lower fees?

Should RAPs also be consulted when Heritage Advisors undergo their Desktop Assessment during the CHMP process?

More information

Download the Discussion Paper

Aboriginal Cultural Heritage Legislation

Find out more on our legislation page.

Submissions now closed

Submissions closed on 30 November. If you have questions about the submission process, email vahc@dpc.vic.gov.au

Submission information was as follows:

- Submissions do not have to deal with the whole Act.

- Only write about the parts of the Act or the themes which most interest you.

- The questions and proposed legislative changes in this discussion paper are posed as a starting point. Multiple proposals for change can be submitted on the same topic.

- The proposals contained in this paper are not intended to limit responses.

Updated